Trusting third party SDKs

Update 2020: Google Chrome has fixed this issue

Third-party SDKs can often easily be modified while you download them! Using a simple person-in-the-middle attack, anyone in the same network can insert malicious code into the library, and with that into your application, as a result running in your user’s pockets.

31% of the most popular closed-source iOS SDKs are vulnerable to this attack, as well as a total of 623 libraries on CocoaPods. As part of this research I notified the affected parties, and submitted patches to CocoaPods to warn developers and SDK providers.

What are the potential consequences of a modified SDK?

It’s extremely dangerous if someone modifies an SDK before you install it. You are shipping your app with that code/binary. It will run on thousands or millions of devices within a few days, and everything you ship within your app runs with the exact same privileges as your app.

That means any SDK you include in your app has access to:

- The same keychain your app has access to

- Any folders/files your app has access to

- Any app permissions your app has, e.g. location data, photo library access

- iCloud containers of your app

- All data your app exchanges with a web server, e.g. user logins, personal information

Apple enforces iOS app sandboxing for good reasons, so don’t forget that any SDK you include in your app runs inside your app’s sandbox, and has access to everything your app has access to.

What’s the worst that a malicious SDK could do?

- Steal sensitive user data, basically add a keylogger for your app, and record every tap

- Steal keys and user’s credentials

- Access the user’s historic location data and sell it to third parties

- Show phishing pop-ups for iCloud, or other login credentials

- Take pictures in the background without telling the user

The attack described here shows how an attacker can use your mobile app to steal sensitive user data.

Web Security 101

To understand how malicious code can be bundled into your app without your permission or awareness, I will provide necessary background to understanding how a MITM attack works and how to avoid it.

The information below is vastly simplified, as I try to describe things in a way that a mobile developer without too much network knowledge can get a sense of how things work and how they can protect themselves.

HTTPS vs HTTP

HTTP: Unencrypted traffic, anybody in the same network (WiFi or Ethernet) can easily listen to the packets. It’s very straightforward to do on unencrypted WiFi networks, but it’s actually almost as easy to do so on a protected WiFi or Ethernet network. There is no way for your computer to verify the packets came from the host you requested data from; Other computers can receive packets before you, open and modify them and send the modified version to you.

HTTPS: With HTTPS traffic other hosts in the network can still listen to your packets, but can’t open them. They still get some basic metadata like the host name, but no details (like the body, full URL, …). Additionally your client also verifies that the packets came from the original host and that no one on the way there modified the content. HTTPS is based on TLS.

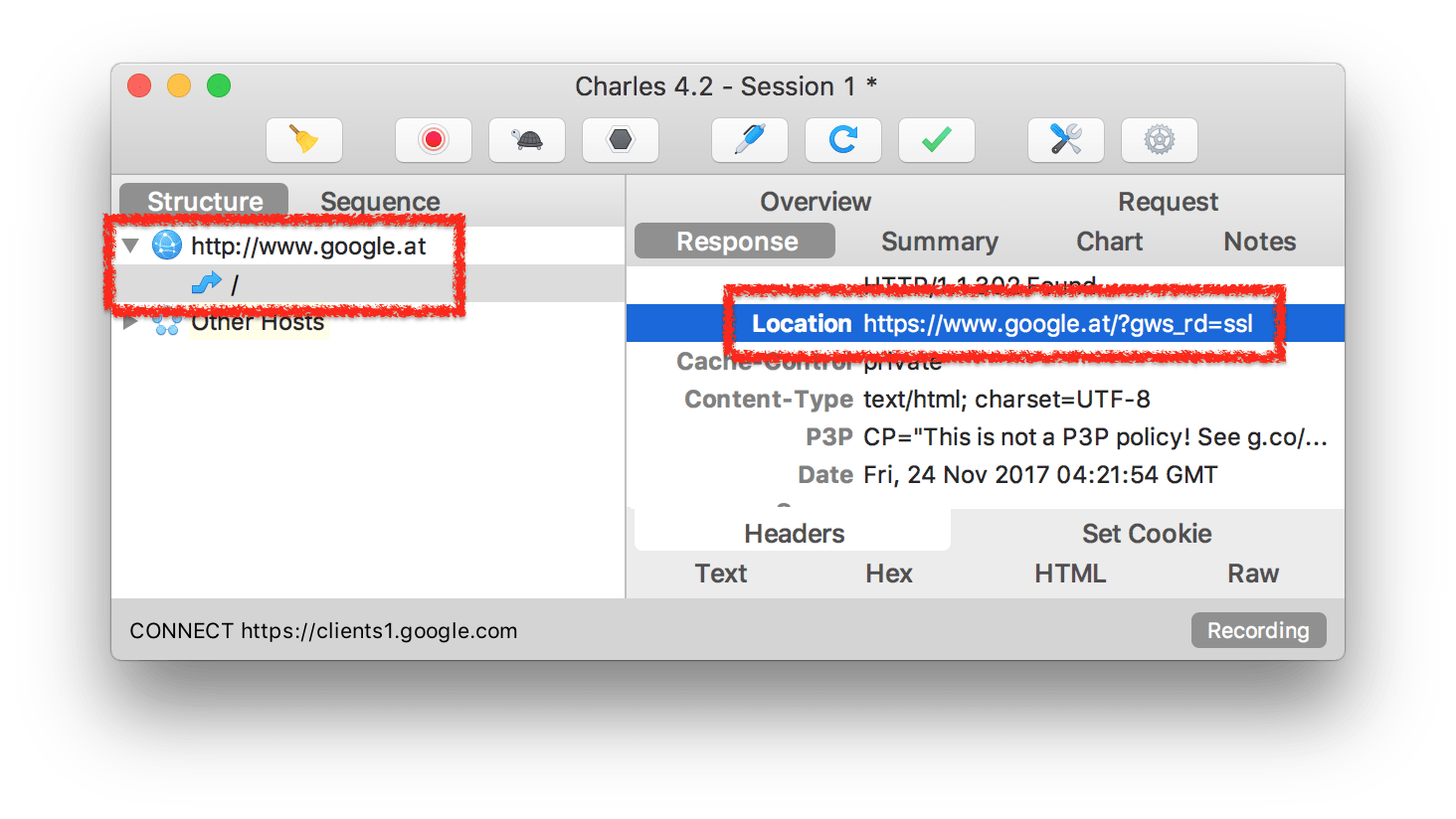

How a browser switches from HTTP to HTTPS

Enter “http://google.com” in your web browser (make sure to use “http”, not “https”). You’ll see how the browser automatically switches from the unsafe “http” protocol to “https”.

This switch doesn’t happen in your browser but comes from the remote server (google.com), as your client (in this case the browser) can’t know what kind of protocol is supported by the host. (Exception for hosts that make use of HSTS)

The initial request happens via “http”, so the server has no choice but to respond in clear text “http” to tell the client to switch over to the secure “https” protocol with a “301 Moved Permanently” response code.

You probably already see the problem here: since the response is being sent in clear text also, an attacker can modify that particular packet and replace the redirect destination URL to stay unencrypted “http”. This is called SSL Stripping, and we’ll talk more about this later.

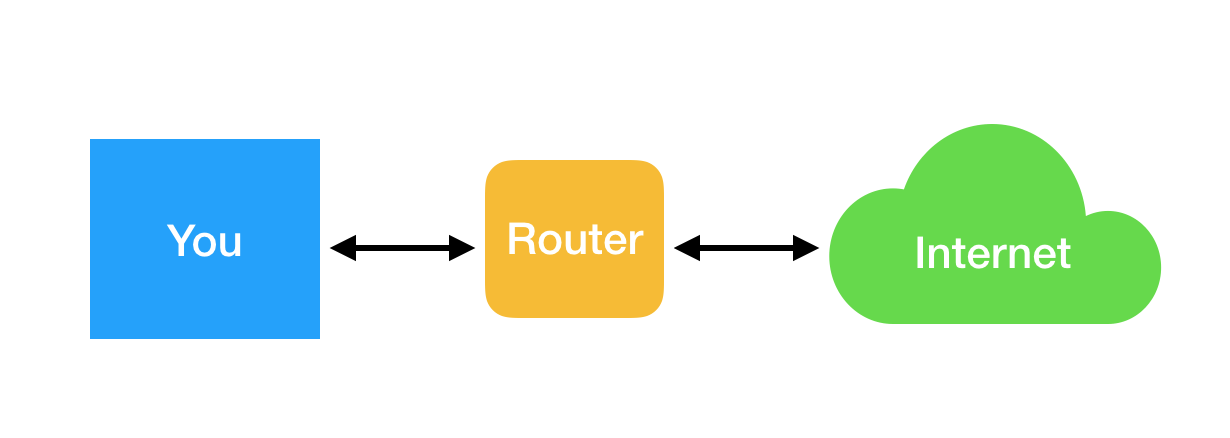

How network requests work

Very simplified, network requests work on multiple layers. Depending on the layer, different information is available on how to route a packet:

- The lowest layer (Data Link Layer) uses MAC addresses to identify hosts in a network

- The layer above (Network Layer) uses IP addresses to identify hosts in the network

- The layers above add port information and the actual message content

If you’re interested, you can learn how the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model works, in particular the implementation TCP/IP (e.g. http://microchipdeveloper.com/tcpip:tcp-ip-five-layer-model).

So, if your computer now sends a packet to the router, how does the router know where to route the packet based on the first layer (MAC addresses)? To solve this problem, the router uses a protocol called ARP (Address Resolution Protocol).

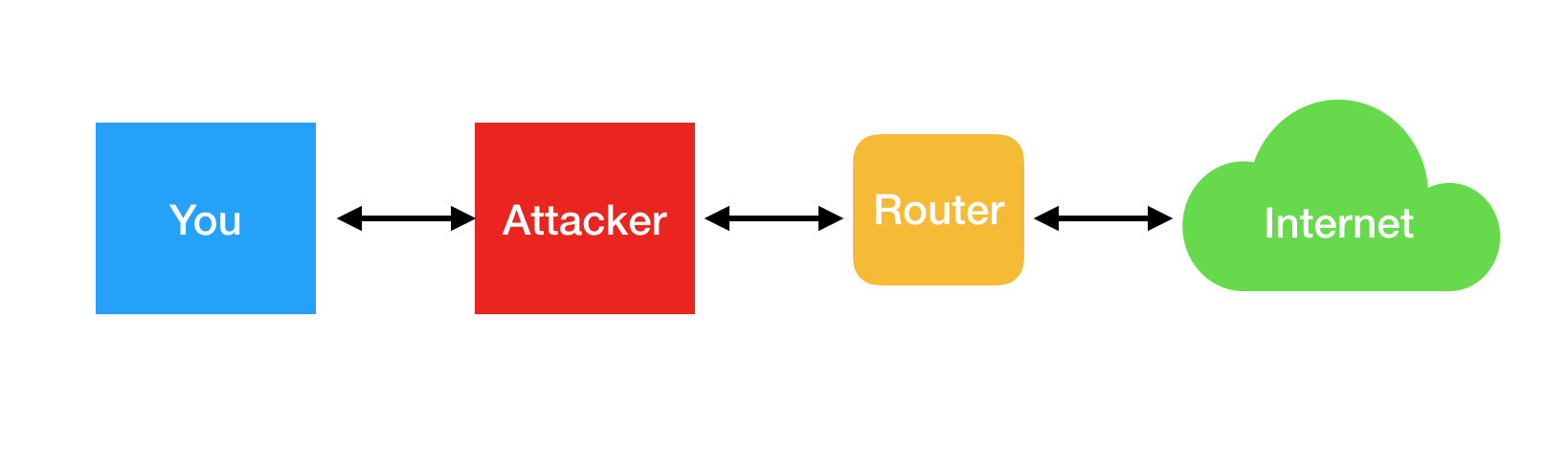

How ARP works and how it can be abused

Simplified, the devices in a network use ARP mapping to remember where to send packets of a certain MAC address. The way ARP works is simple: if a device wants to know where to send a packet for a certain IP address, it asks everyone in the network: “Which MAC address belongs to this IP?”. The device with that IP then replies to this message ✋

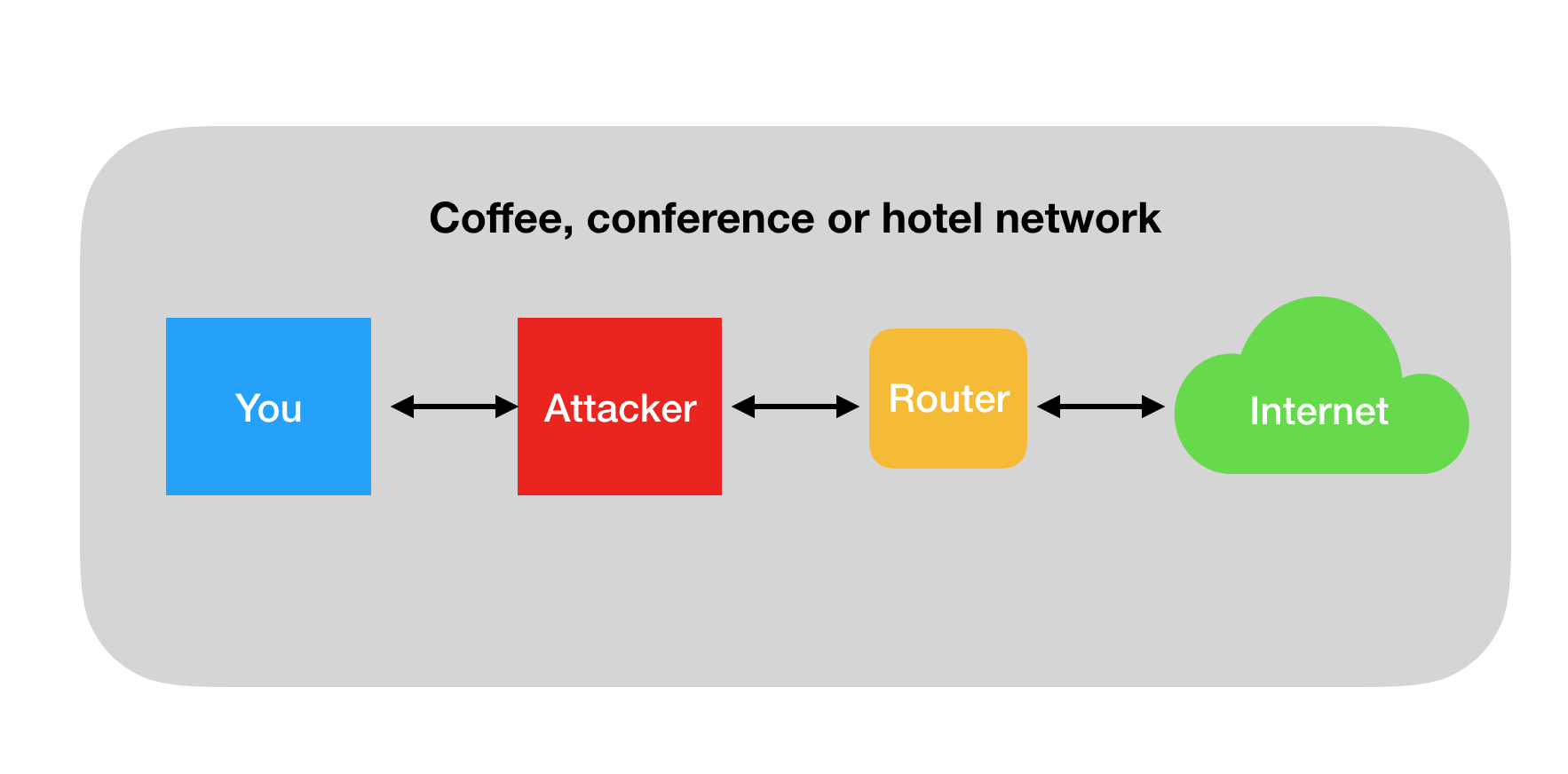

Unfortunately, there is no way for a device to authenticate the sender of an ARP message. Therefore an attacker can be fast in responding to ARP announcements sent by another device, basically saying: “Hey, please send all packets that should go to IP address X to this MAC address”. The router will remember that and use that information for all future requests. This is called “ARP poisoning.”

See how all packets are now routed through the attacker instead of going directly from the remote host to you?

As soon as the packets go through the attacker’s machine there is some risk. It’s the same risk you have when trusting your ISP or a VPN service: if the services you use are properly encrypted, they can’t really know details about what you’re doing or modify packets without your client (e.g. browser) noticing. As mentioned before there is still basic information that will always be visible such as certain metadata (e.g. the host name).

If there are web packets that are unencrypted (say HTTP) the attacker can not only look inside and read their content, but can also modify anything in there with no way of detecting the attack.

Note: the technique described above is different from what you might have read about the security issues with public WiFi networks. Public WiFis are a problem because everybody can just read whatever packets are flying through the air, and if they’re unencrypted HTTP, it’s easy to read what’s happening. ARP pollution works on any network, no matter if public or not, or if WiFi or ethernet.

Let’s see this in action

Let’s look into some SDKs and how they distribute their files, and see if we can find something.

CocoaPods

Open source Pods: CocoaPods uses git under the hood to download code from code hosting services like GitHub. The git:// protocol uses ssh://, which is similarly encrypted to HTTPS. In general, if you use CocoaPods to install open source SDKs from GitHub, you’re pretty safe.

Closed source Pods: When preparing this blog post, I noticed that Pods can define a HTTP URL to reference binary SDKs, so I submitted multiple pull requests (1 and 2) that got merged and released with CocoaPods 1.4.0 to show warnings when a Pod uses unencrypted http.

Crashlytics SDK

Crashlytics uses CocoaPods as the default distribution, but has 2 alternative installation methods: the Fabric Mac app and manual installation, which are both https encrypted, so not much we can do here.

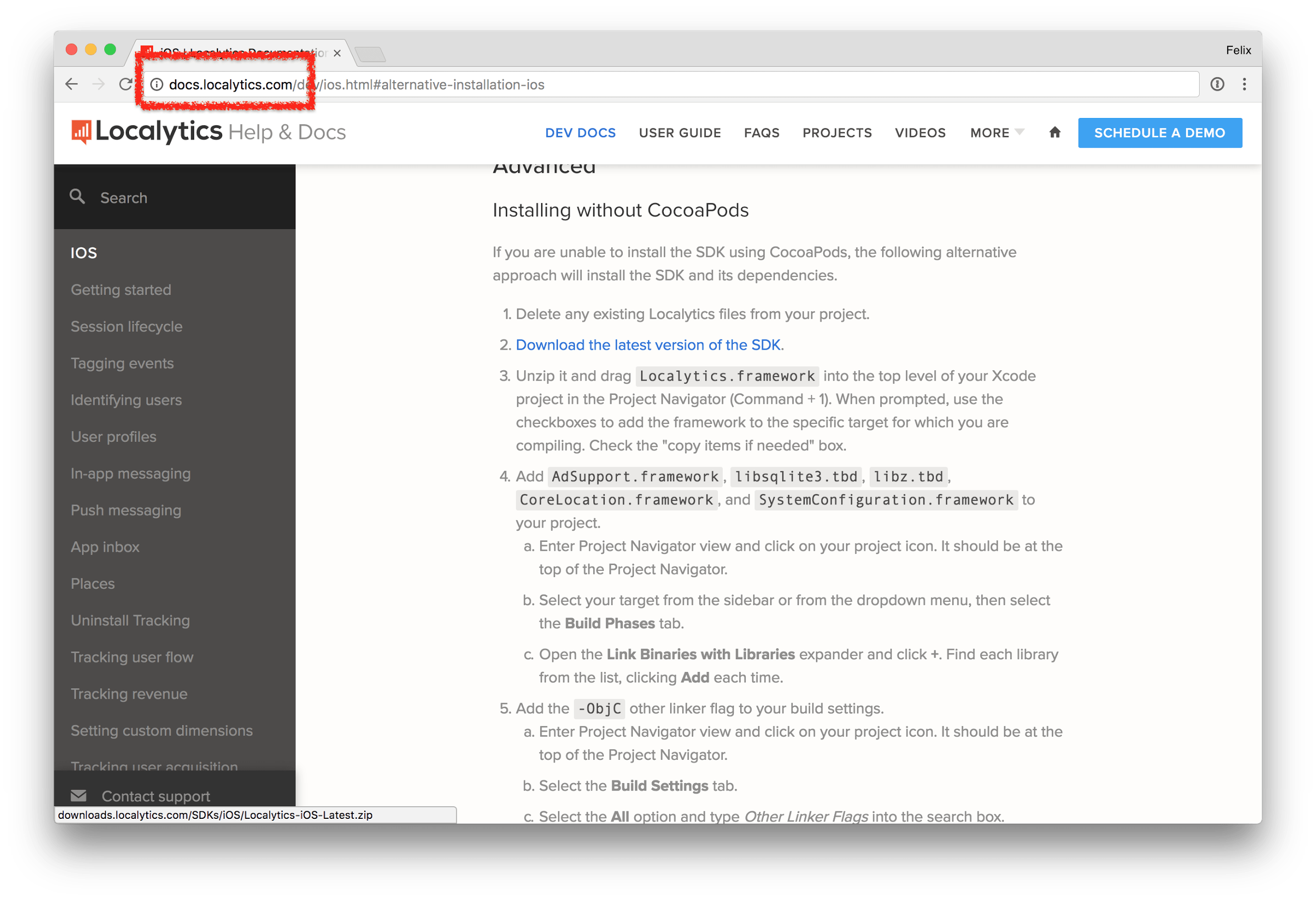

Localytics

Let’s look at a sample SDK, the docs page is unencrypted via http (see the address bar)

So you might think: “Ah, I’m just reading the docs here, I don’t care if it’s unencrypted”. The problem here is that the download link (in blue) is also transferred as part of the website, meaning an attacker can easily replace the https:// link with http://, making the actual file download unsafe.

Alternatively an attacker could just switch the https:// link to the attacker’s URL that looks similar

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/localytics-sdk/sdk.zip

- https://s3.amazonaws.com/localytics-sdk-binaries/sdk.zip

And there is no good way for the user to verify that the specific host, URL or S3 bucket belongs to the author of the SDK.

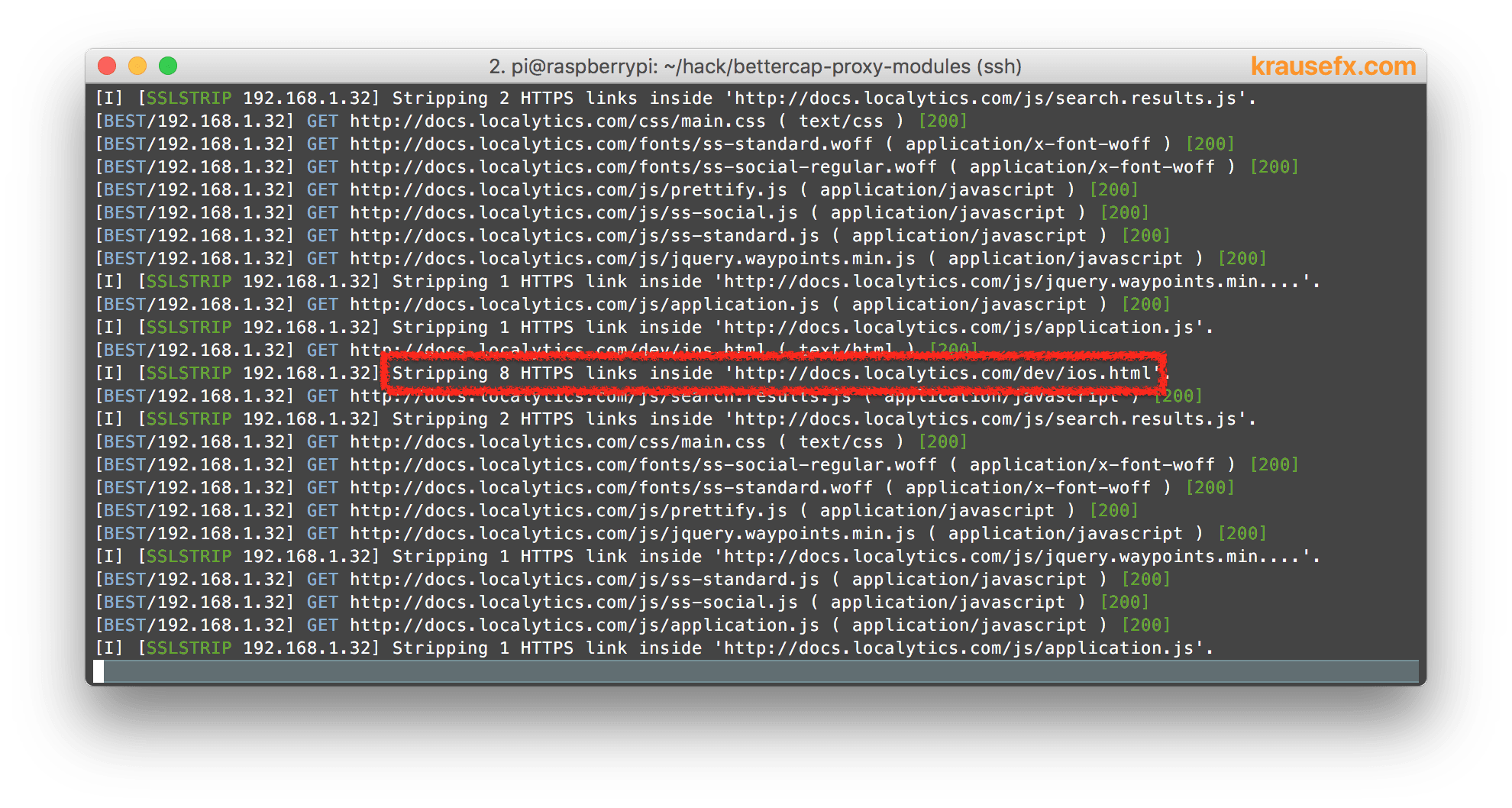

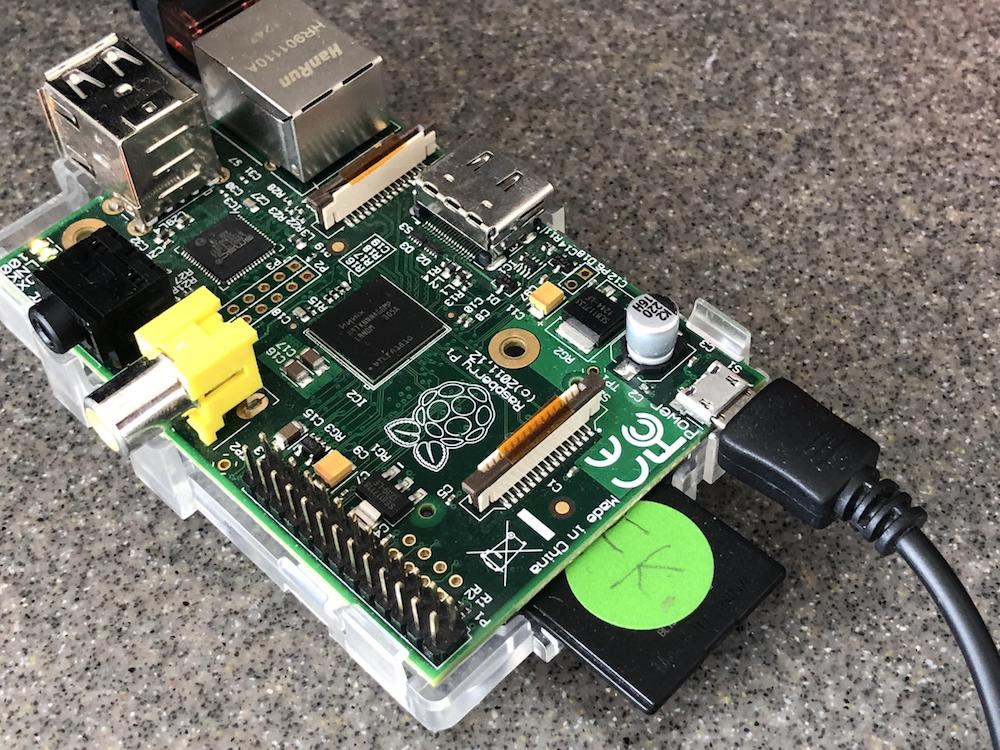

To verify this I’ve set up my Raspberry PI to intercept the traffic and do various SSL Stripping (downgrading of HTTPS connections to HTTP) across the board, from JavaScript files, to image resources and of course download links.

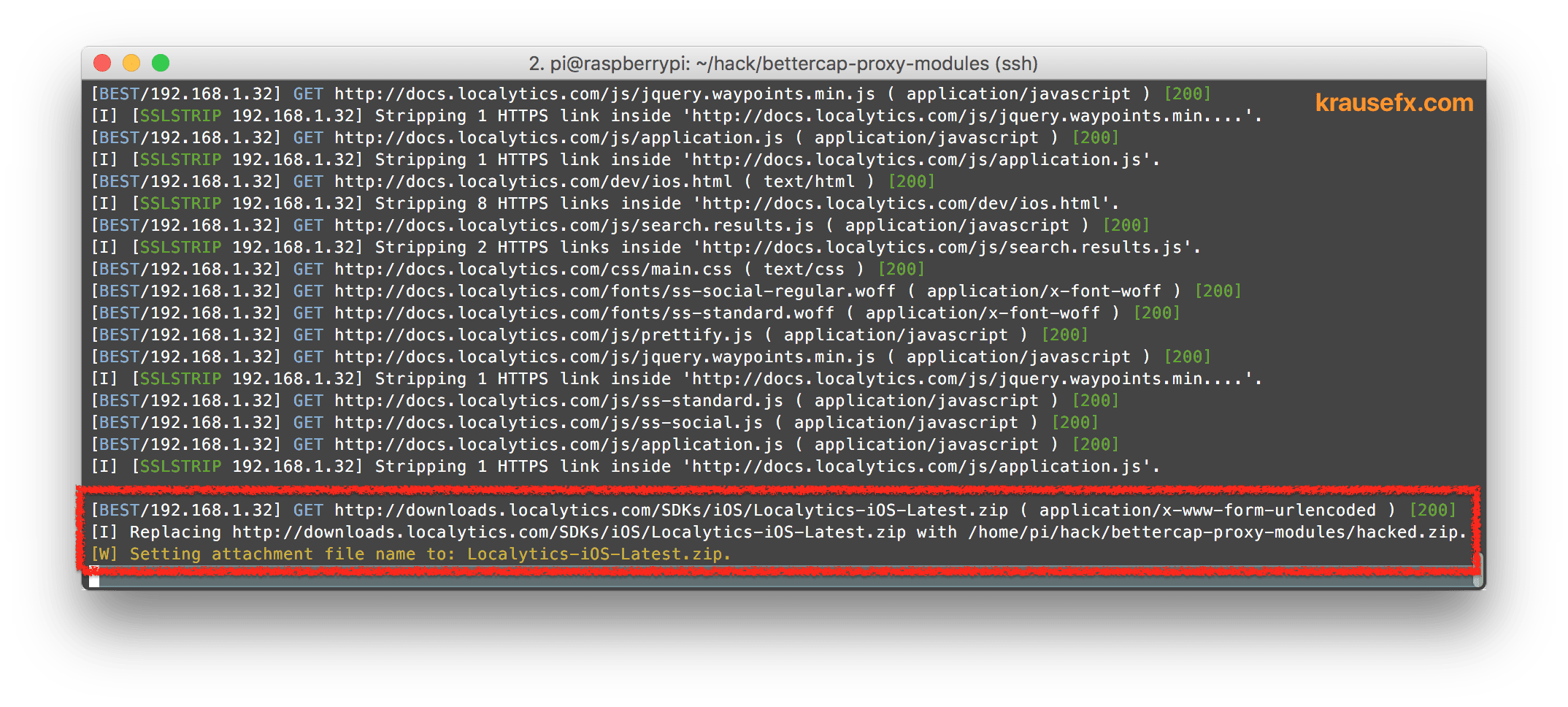

Once the download link was downgraded to HTTP, it’s easy to replace the content of the zip file as well:

Replacing HTML text on the fly is pretty easy, but how can an attacker replace the content of a zip file or binary?

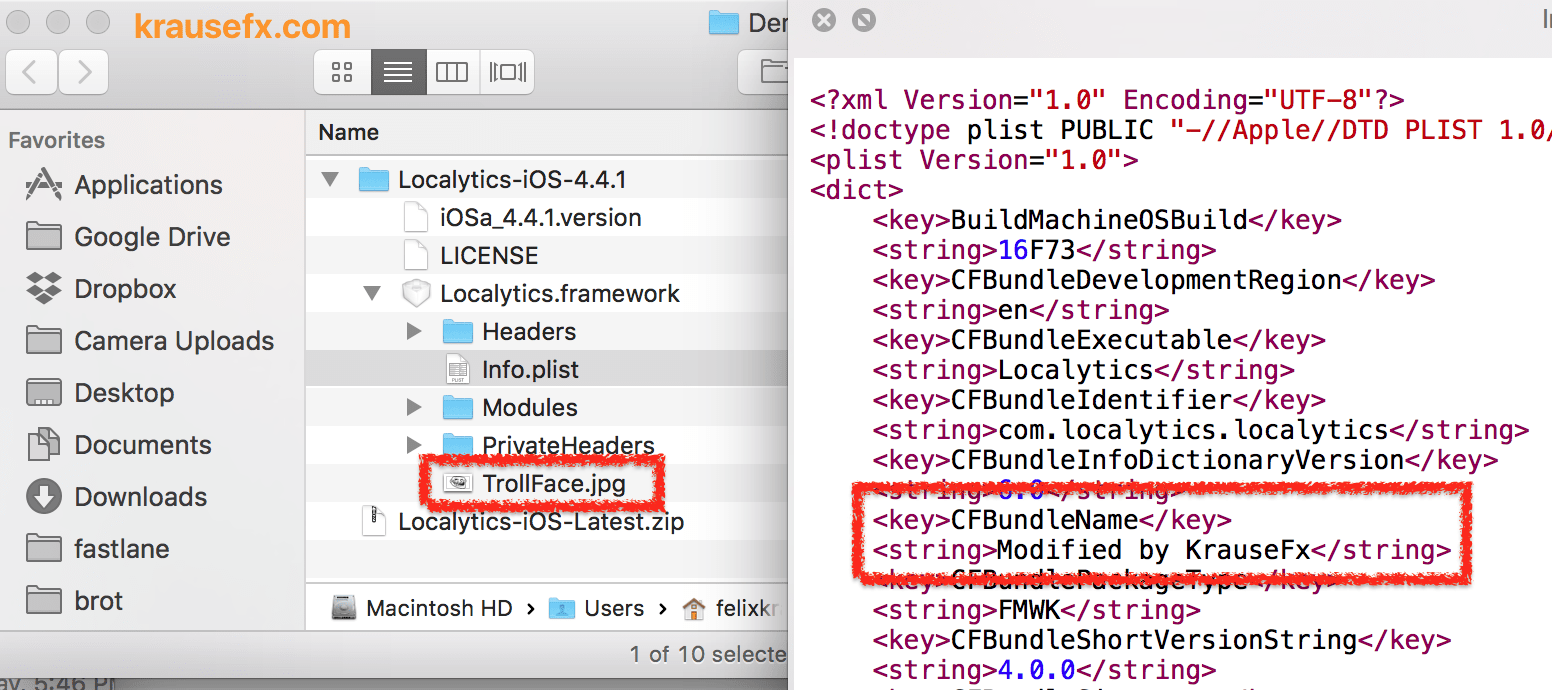

- The attacker downloads the original SDK

- The attacker inserts malicious code into the SDK

- The attacker compresses the modified SDK

- The attacker looks at packets coming by, and jumps in to replace any zip file matching a certain pattern with the file the attacker prepared

(This is the same approach used by the image replacement trick: Every image that’s transferred via HTTP gets replaced by a meme)

As a result, the downloaded SDK might include additional files or code that was modified:

For this attack to work, the requirements are:

- The attacker is in the same network as you

- The docs page is unencrypted and allows SSL Stripping on all links

Localytics resolved the issue after disclosing it, so both the docs page, and the actual download are now HTTPS encrypted.

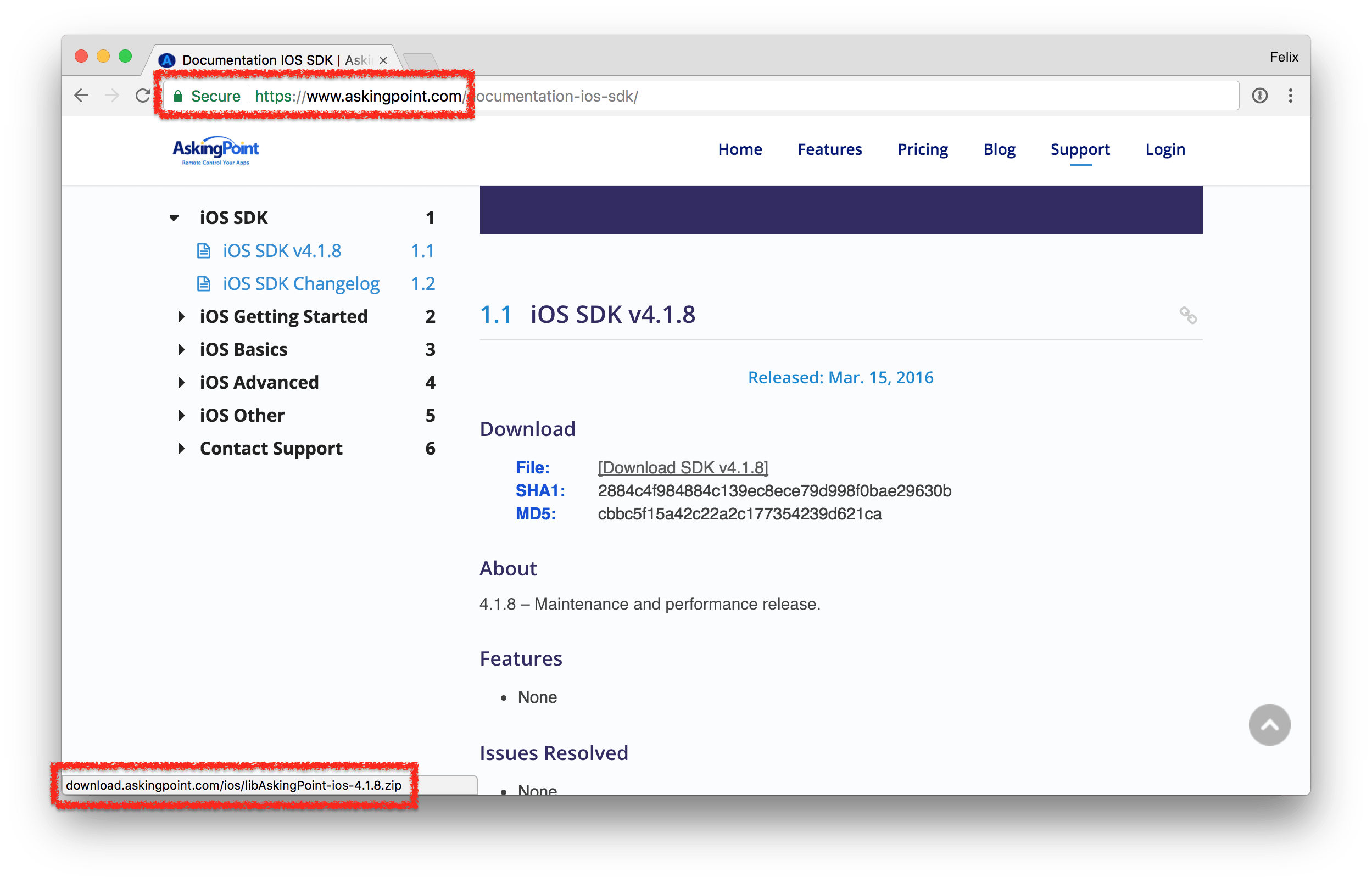

AskingPoint

Looking at the next SDK, we have a HTTPS encrypted docs page, looking at the screenshot, this looks secure:

Turns out, the HTTPS based website links to an unencrypted HTTP file, and web browsers don’t warn users in those cases (some browsers already show a warning if JS/CSS files are downloaded via HTTP). It’s almost impossible for the user to detect that something is going on here, except if they were to actually manually compare the hashes provided. As part of this project, I filed a security report for both Google Chrome (794830) and Safari (rdar://36039748) to warn the user of unencrypted file downloads on HTTPS sites. (This has been resolved by Google Chrome)

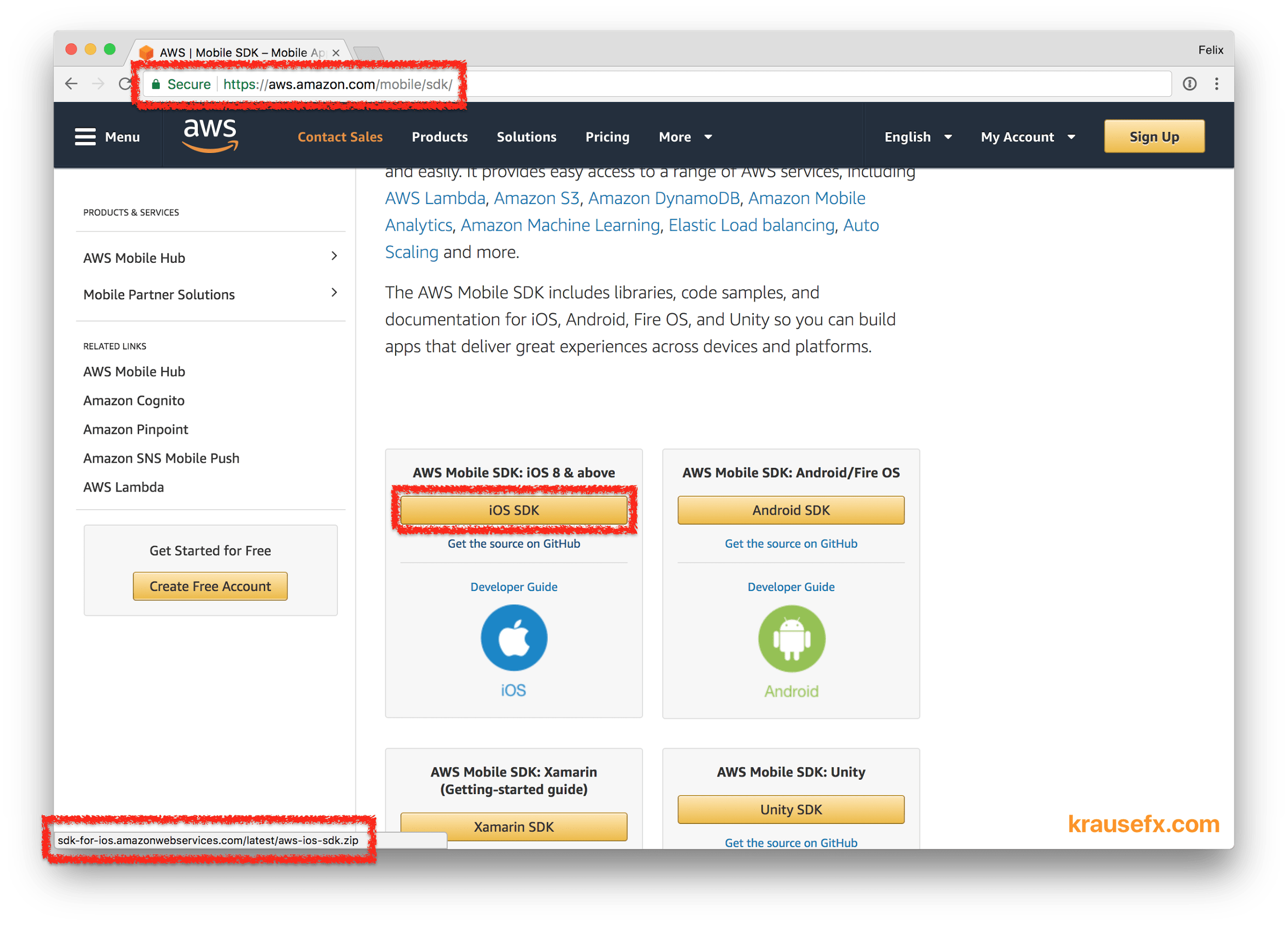

AWS SDK

At the time I was conducting this research, the AWS iOS SDK download page was HTTPS encrypted, however linked to a non-encrypted zip download, similarly to the SDKs mentioned before. The issue has been resolved after disclosing it to Amazon.

Putting it all together

Thinking back about the iOS privacy vulnerabilities mentioned before (iCloud phishing, location access through pictures, accessing camera in background), what if we’re not talking about evil developers trying to trick their users… What if we talk about attackers that target you, the iOS developer, to reach millions of users within a short amount of time?

Attacking the developer

What if an SDK gets modified as you download it using a person-in-the-middle attack, and inserts malicious code that breaks the user’s trust? Let’s take the iCloud phishing popup as an example, how hard would it be to use apps from other app developers to steal passwords from the user for you, and send them to your remote server?

In the video below you can see a sample iOS app that shows a mapview. After downloading and adding the AWS SDK to the project, you can see how malicious code is being executed, in this case an iCloud phishing popup is shown and the cleartext iCloud password can be accessed and sent to any remote server.

The only requirement for this particular attack to work is that the attacker is in the same network as you (e.g. stays in the same conference hotel). Alternatively this attack can also be done by your ISP or the VPN service you use. My Mac runs the default macOS configuration, meaning there is no proxy, custom DNS or VPN set up.

Setting up an attack like this is surprisingly easy using publicly available tools that are designed to do automatic SSL Stripping, ARP pollution and replacing of content of various requests. If you’ve done it before, it will take less than an hour to set everything up on any computer, including a Raspberry Pi, which I used for my research. The total costs for the whole attack is therefore less than $50.

I decided not to publish the names of all the tools I used, nor the code I wrote. You might want to look into well-known tools like sslstrip, mitmproxy and Wireshark

Running arbitrary code on the developer’s machine

The previous example injected malicious code into the iOS app using a hijacked SDK. Another attack vector is the developer’s Mac. Once an attacker can run code on your machine, and maybe even has remote SSH access, the damage could be significant:

- Activate remote SSH access for the admin account

- Install keylogger to get admin password

- Decrypt the keychain using the password, and send all credentials to remote server

- Access local secrets, like AWS credentials, CocoaPods & RubyGems push tokens and more

- If a developer now has a popular CocoaPod, you can spread more malicious code through their SDKs

- Access literally any file and database on your Mac, including iMessage conversations, emails and source code

- Record the user’s screen without them knowing

- Install a new root SSL certificate, allowing the attacker to intercept most of your encrypted network requests

To prove that this is working, I looked into how to inject malicious code in a shell script developers run locally, in this case BuddyBuild:

- Same requirements as in the previous example, attacker needs to be in the same network

- BuddyBuild docs told users to

curlan unencrypted URL piping the content over tosh, meaning any code thecurlcommand returns will be executed - The modified

UpdateSDKis provided by the attacker (Raspberry PI), and asks for the admin password (normally BuddyBuild’s update script doesn’t ask for this) - Within under a second, the malicious script does the following

- Enable SSH remote access for the current account

- Install & setup a keylogger that auto-starts when you login

Once the attacker has the root password and SSH access, they can do anything listed above.

BuddyBuild resolved the issue after reporting it.

How realistic is such an attack?

Very! Open your Network settings on the Mac, and take a look at the list of WiFi networks your Mac was connected to. In my case, my MacBook was connected to over 200 hotspots. How many of them can you fully trust? Even in a trustworthy network, there could still be other machines that got hacked previously which are doing remote controlled attacks (see section above)

SDKs and developer tools become more and more a target for attackers. Some examples from the past years:

- Xcode Ghost affected about 4,000 iOS apps, including WeChat:

- Attacker gains remote access to any phone running the app

- Show phishing popups

- Access and modify the clipboard (dangerous when using password managers)

- The NSA worked on finding iOS exploits

- Pegasus: malware for non-jailbroken iPhones, used by governments

- KeyRaider: Only affected jailbroken iPhones, but still stole user-credentials from over 200,000 end-users

- Just the last few weeks, there have been multiple posts about how this affects web projects also (e.g. 1, 2)

and many, many more. Another approach is getting access to the download server (e.g. S3 bucket using access keys) and replacing the binary. This happened multiple times in the past few years, for example Transmission Mac app incident. This opens a whole new level of area of attack, which I didn’t cover in this blog post.

Conferences, hotels, coffee shops

Every time you connect to the WiFi at a conference, hotel or coffee shop, you become an easy target. Attackers know that there is a high number of developers during conferences and can easily make use of the situation.

How can SDK providers protect their users?

This would go out of scope for this blog post. Mozilla offers a security guide that’s a good starting point. Mozilla provides a tool called observatory that will do some automatic checks of the server settings and certificates.

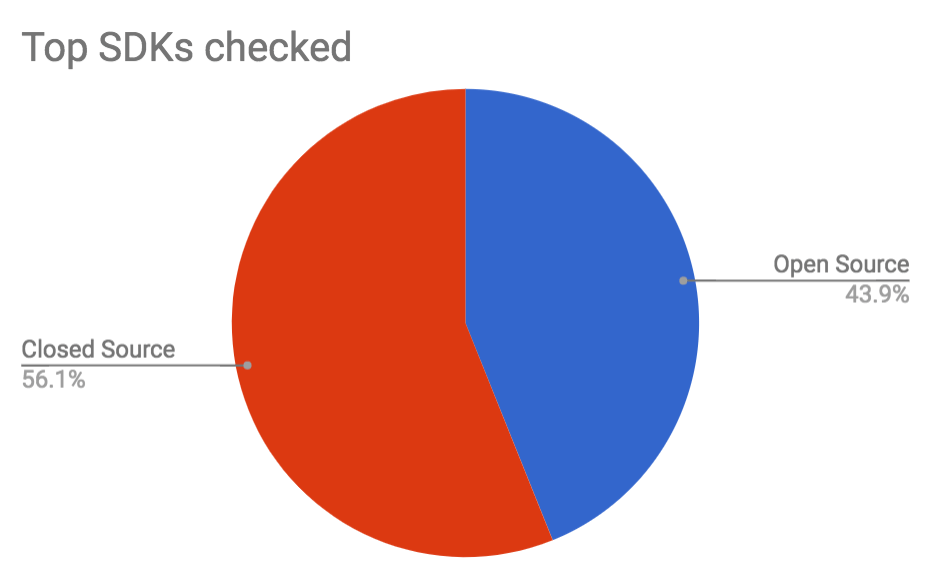

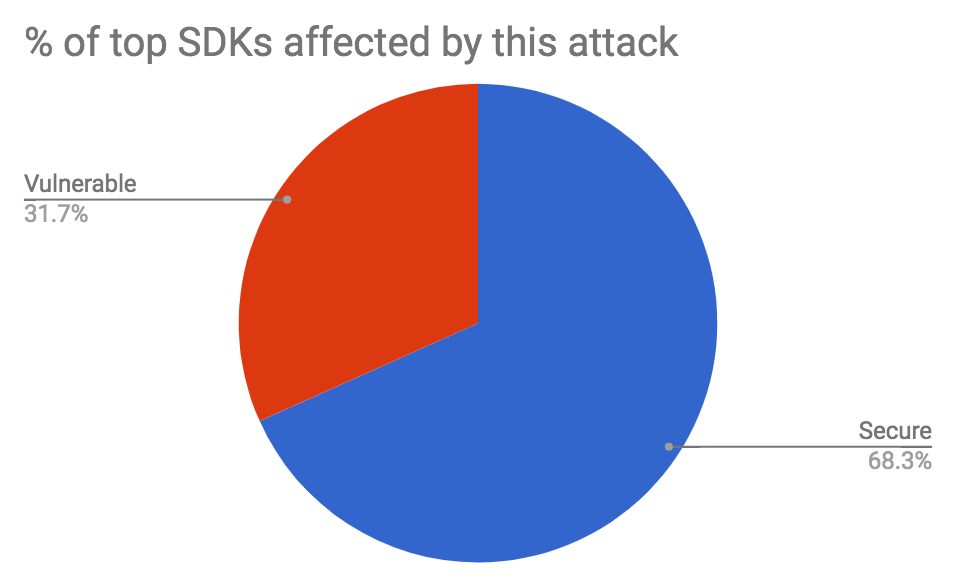

How many of the most popular SDKs are affected by this vulnerability?

While doing this research starting on 23rd November 2017, I investigated 41 of the most popular mobile SDKs according to AppSight (counting all Facebook and Google SDKs as one, as they share the same installation method - skipping SDKs that are open source on GitHub)

- 41 SDKs checked

- 23 are closed source and you can only download binary files

- 18 of those are open source (all of them on GitHub)

- 13 are an easy target of person-in-the-middle attacks without any indication to the user

- 10 of them are closed source SDKs

- 3 of them are open source SDKs, meaning the user can either download the SDK via unencrypted HTTP from the official website, or securely clone the source code from GitHub

- 5 of the 41 SDKs offer no way to download the SDK securely, meaning they don’t support any HTTPS at all, nor use a service that does (e.g. GitHub)

- 31% of the top used SDKs are easy targets for this attack

- 5 additional SDKs required an account to download the SDK (do they have something to hide?)

I notified all affected in November/December 2017, giving them 2 months to resolve the issue before publicly talking about it. Out of the 13 affected SDKs

- 1 resolved the issue within three business days

- 5 resolved the issue within a month

- 7 SDKs are still vulnerable to this attack at the time of publishing this post.

The SDK providers that are still affected haven’t responded to my emails, or just replied with “We’re gonna look into this” - all of them in the top 50 most most-used SDKs.

Looking through the available CocoaPods, there are a total of 4,800 releases affected, from a total of 623 CocoaPods. I generated this data locally using the Specs repo with the command grep -l -r '"http": "http://' *.

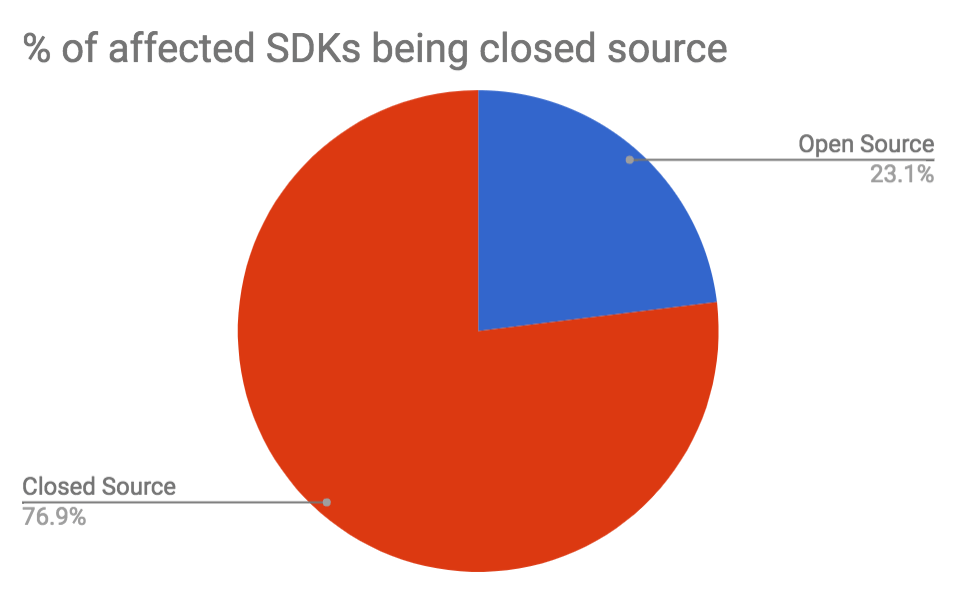

Open Source vs Closed Source

Looking the number above, you are much likely to be affected by attacks if you use closed source SDKs. More importantly: When an SDK is closed source, it’s much harder for you to verify the integrity of the dependency. As you probably know, you should always check the Pods directory into version control, to detect changes and be able to audit your dependency updates. 100% of the open source SDKs I investigated can be used directly from GitHub, meaning even the 3 SDKs affected are not actually affected if you make sure to use the version on GitHub instead of taking it from the provider’s website.

Based on the numbers above it is clear that in addition to not being able to dive into the source code for closed source SDKs you also have a much higher risk of being attacked. Not only person-in-the-middle attacks, but also:

- The attacker gains access to the SDK download server

- The company providing the SDK gets compromised

- The local government forces the company to include back-doors

- The company providing the SDK is evil and includes code & tracking you don’t want

You are responsible for the binaries you ship! You have to make sure you don’t break your user’s trust, European Union data protection laws (GDPR) or steal the user’s credentials via a malicious SDK.

Wrapping up

As a developer, it’s our responsibility to make sure we only ship code we trust. One of the easiest attack vectors right now is via malicious SDKs. If an SDK is open source, hosted on GitHub, and is installed via CocoaPods, you’re pretty safe. Be extra careful with bundling closed-source binaries or SDKs you don’t fully trust.

Since this type of attack can be done with little trace, you will not be able to easily find if your codebase is affected. By using open source code, we as developers can better protect ourselves, and with it, our customers.

Check out my other privacy and security related publications.

Update: Crowdsourced list of SDKs

Many people asked for a list of affected SDKs. Instead of publishing a static list, I decided to setup a repo where every developer can add and update SDKs, check it out on trusting-sdks/https.

Thank you

Special thanks to Manu Wallner for doing the voice recordings for the video.

Special thanks to my friends for providing feedback on this post: Jasdev Singh, Dave Schukin, Manu Wallner, Dominik Weber, Gilad, Nicolas Haunold and Neel Rao.

Tags: security, privacy, sdks | Edit on GitHub