Scaling open source communities

Not too long ago I started an open source project called fastlane. Just a month after publishing, it had 1000+ stars on GitHub and was beginning to get used by lots of serious tech companies around the world. Soon I was the sole maintainer of a project getting 10+ PRs/day, and spending 8+hrs/day reviewing PRs and replying to questions on GitHub. This is the story of some of the challenges I faced when scaling the project to where it is today: a OSS project stewarded by Twitter and now Google, with over 12k commits, 13k stars, 500+ contributors, and one of the top 25 most active open source projects on GitHub (spoiler alert: I didn’t do it alone).

Different stages of open source projects

Stage 1: Putting source code on GitHub

About 40% of all repositories on GitHub have 0 stars and don’t gain a lot of traction. Most of those repositories don’t have a single GitHub issue or Pull Request. For example, a very early version of fastlane snapshot was called rScreenshooter and has almost no engagement on GitHub.

Stage 2: Developers start using your software

It’s tough to know how many people use your code until you get your first Issue or PR. Receiving your first PR is an amazing feeling: Complete strangers care enough about your project that they gave it a try, and even dived into the code to work on an improvement, and send it back to you. However, simple PRs like a doc changes aren’t signals that a developer is using your code. Only when a pull request changes the software’s behavior you know it’s being used, and it’s a great feeling. For fastlane this was the case a PR from foozmeat that improves the design of the app’s summary. Not only was that a great change, but also was it from someone at Panic.

Stage 3: Project is popular and the go-to solution in its field

Even more exciting times start when your project becomes the de-facto standard for the problem your software solves. In my experience you first realise it when someone on Twitter asks on how to solve a problem, and multiple people reply with a link to your GitHub project.

Examples:

Stage 4: Hyper-scale open source projects

If you finally are able to grow your user base wide enough, you might hit a new set of problems. Stage 4 is where the fun begins: you will get hundreds of notifications every day, there will be blog posts that attack your project and there will be commercial versions of your project, maybe even (partly) using your source code. Some of those projects slowly evolved to being in this category (e.g. rails), however more and more projects have a kick-start by being launched as a solid, finished open source project by one of the big companies like Facebook or GitHub.

Examples:

Scaling open source projects is hard

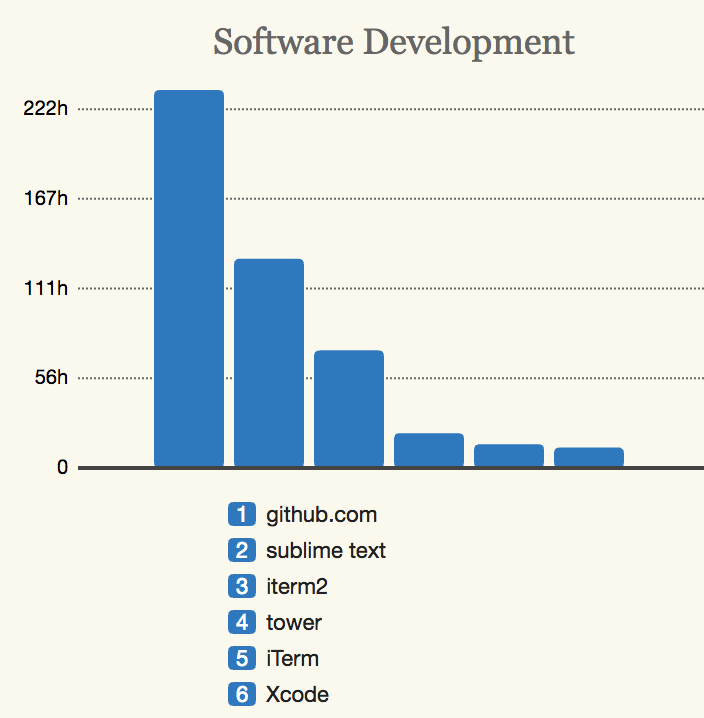

My time spent on GitHub compared to my text editor, with the growing popularity of fastlane, GitHub goes up more and more

My time spent on GitHub compared to my text editor, with the growing popularity of fastlane, GitHub goes up more and more

Keeping the momentum

The bigger your project becomes, the harder it is to keep the innovation you had in the beginning of your project. Suddenly you have to consider hundreds of different use-cases, thousands of production setups and can’t just remove an option, or change a default value.

Handling support for open source projects

Once you pass a few thousand active users, you’ll notice that helping your users takes more time than actually working on your project. People submit all kinds of issues, most of them aren’t actually issues, but feature requests or questions.

Receiving feature requests

How you handle feature requests is up to you, there are various ways projects handle them:

- Let people submit features as issues, and label them as feature request. This way other users can easily find them using the search, and upvote them

- Have a separate page where users can submit and upvote feature requests

- Don’t accept new features, and feature freeze your project

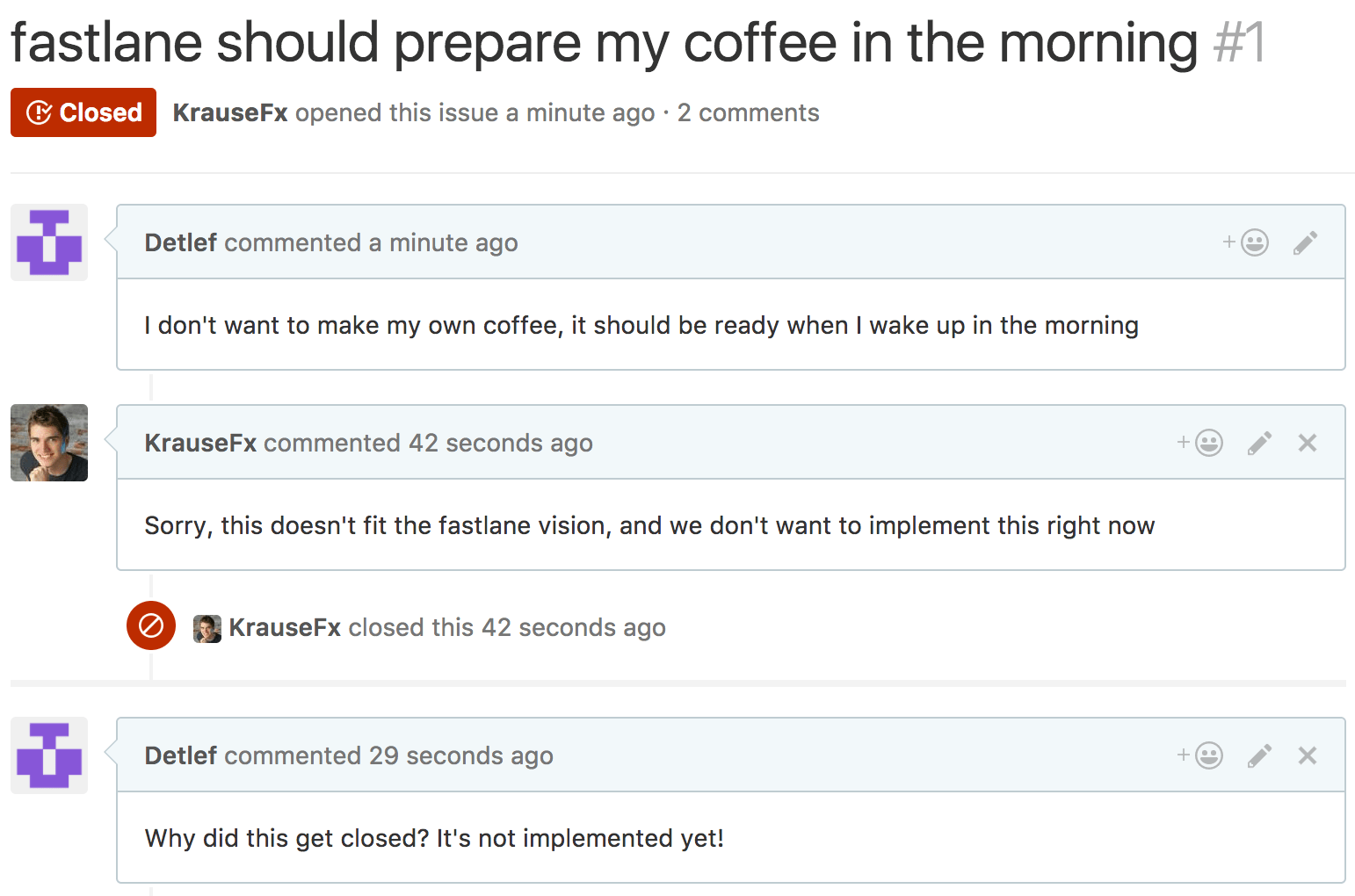

There are very interesting conversations when you close feature requests:

Being in the public spotlight

As a maintainer you are under big pressure when dealing with those kinds of situations. Depending on the conversation, people can tweet screenshots,you might land on HackerNews or cause a shitstorm, causing hundreds of comments by random people on the internet. This distraction leads to many maintainers leaving feature requests open and unanswered, and not dealing with them altogether.

Due to the pressure of having 100% of your activities (both code and conversations) in public, lots of open source maintainers burn out. You can find hundreds of blog articles about software developers sharing their story (most recently “Dear JavaScript”).

Reviewing external PRs

As a maintainer you often have the responsibility to decide what you merge into your project’s code base, and what to reject. Very often these are very difficult decisions, which might hurt other people. When merging code changes that introduce new features or options, the maintainers have to consider the long-term effect of this change:

- The feature has to be supported in future releases.

- The feature has to be tested with all future changes.

- When the feature breaks, very often the project maintainer has to fix it, unless the original author is still available.

- Many users aren’t aware of this, and sometimes people get offended on GitHub when you say “No” to a new flag or option.

In general, reviewing and testing a pull request, takes almost as much time as writing the code for it. As a maintainer you have goals for your project, and work towards them. By receiving external pull requests without any prior discussion on a GitHub issue or mailing list, you have to pause what you currently worked on, to review and test this change without the same context or motivation that the PR author has.

It’s very hard to balance reaching your current goals, and investing time reviewing pull requests that don’t work towards them.

Maintainers stop being users of the project as it grows

This is an interesting phenomenon with many big open source project, including fastlane and CocoaPods: The project was started because the author needed the software for themselves. Suddenly they work on the open source project full-time, stopping the activity they’ve been doing before. With that they stop being a user of their own project. They are not in their own product’s target group any more.

The challenge is to still somehow use the product to feel the user’s pain points, and realize what to focus their time on. For example, fastlane is deployed using fastlane, therefore everyone working on fastlane also uses the product. If that’s not possible for your project, force yourself to onboard your own project from time to time, and go through the whole process.

Information imbalance with your users

Due to the nature of scaling software, there is a big information imbalance between the project maintainers and the users. For you as a maintainer, an issue is “just another issue” (one of hundreds), but for the user, this one issue is everything. This issue is 100% of the interaction with your product, and it’s something they will remember for a long time.

This first hit me when I attended my first WWDC in 2016, and iOS developers came up to me to talk about the GitHub issue they submitted a while back, assume I’d remember the whole conversation. This is not only the case for online interactions, but also when talking with users of your software.

For the maintainer it’s an issue that has to be prioritized and it might not be the most important thing. For the user, it’s everything and might keep them from using your product, and it’s the thing they are going to remember for a really long time.

The healthy way to scale your open source project

Improve your error messages

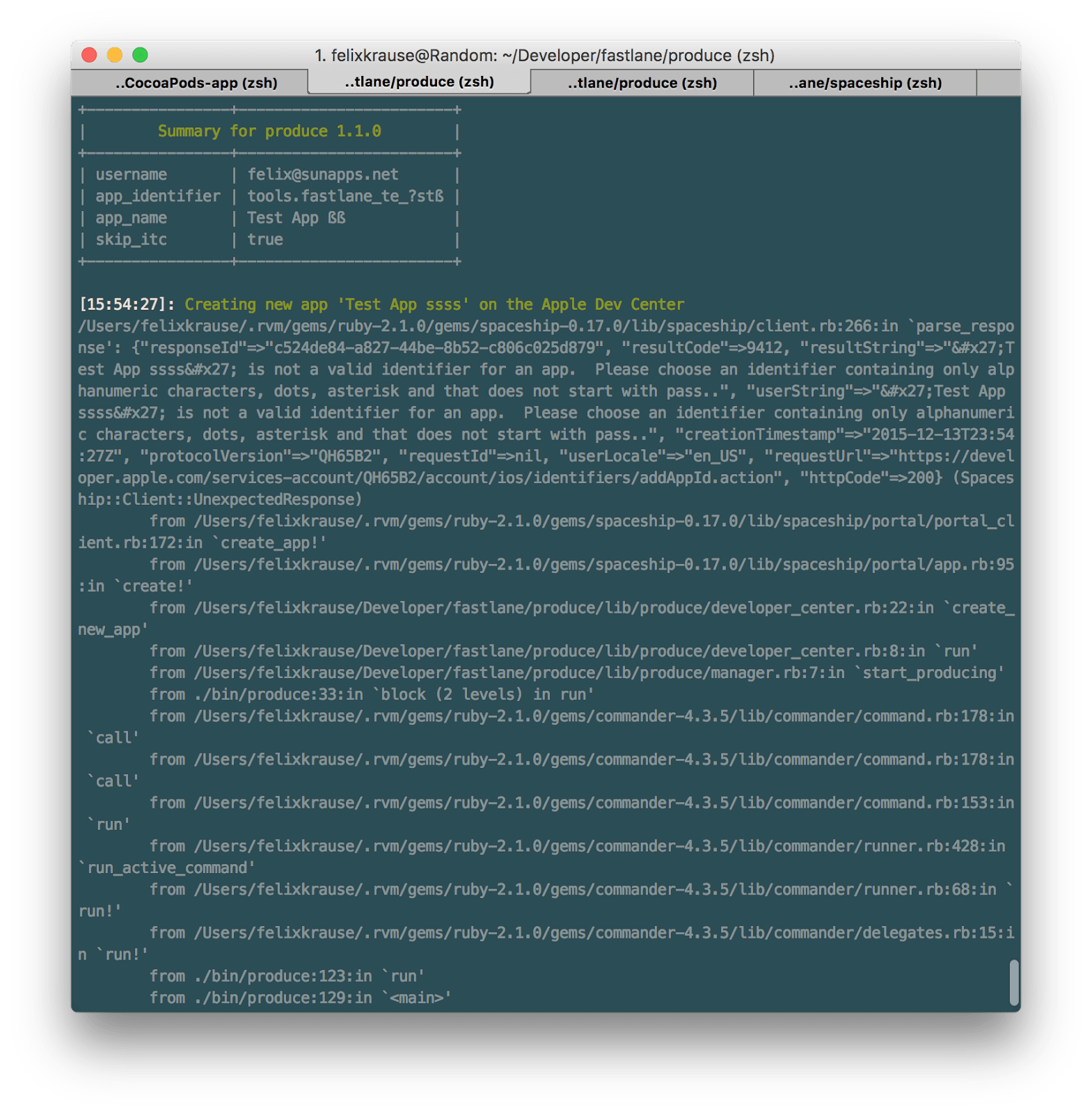

How you handle failures has a big impact on how easy it is for the user to resolve the issue. So many developer tools get that wrong (Thoughts on iOS build tools) and make it incredibly hard for people to use their software.

Before changing fastlane to highlight the actual error message and still showing the stack trace by default

Before changing fastlane to highlight the actual error message and still showing the stack trace by default

After the change: fastlane now color-highlights the actual error message, and hides the stack trace by default, unless it’s a real crash

After the change: fastlane now color-highlights the actual error message, and hides the stack trace by default, unless it’s a real crash

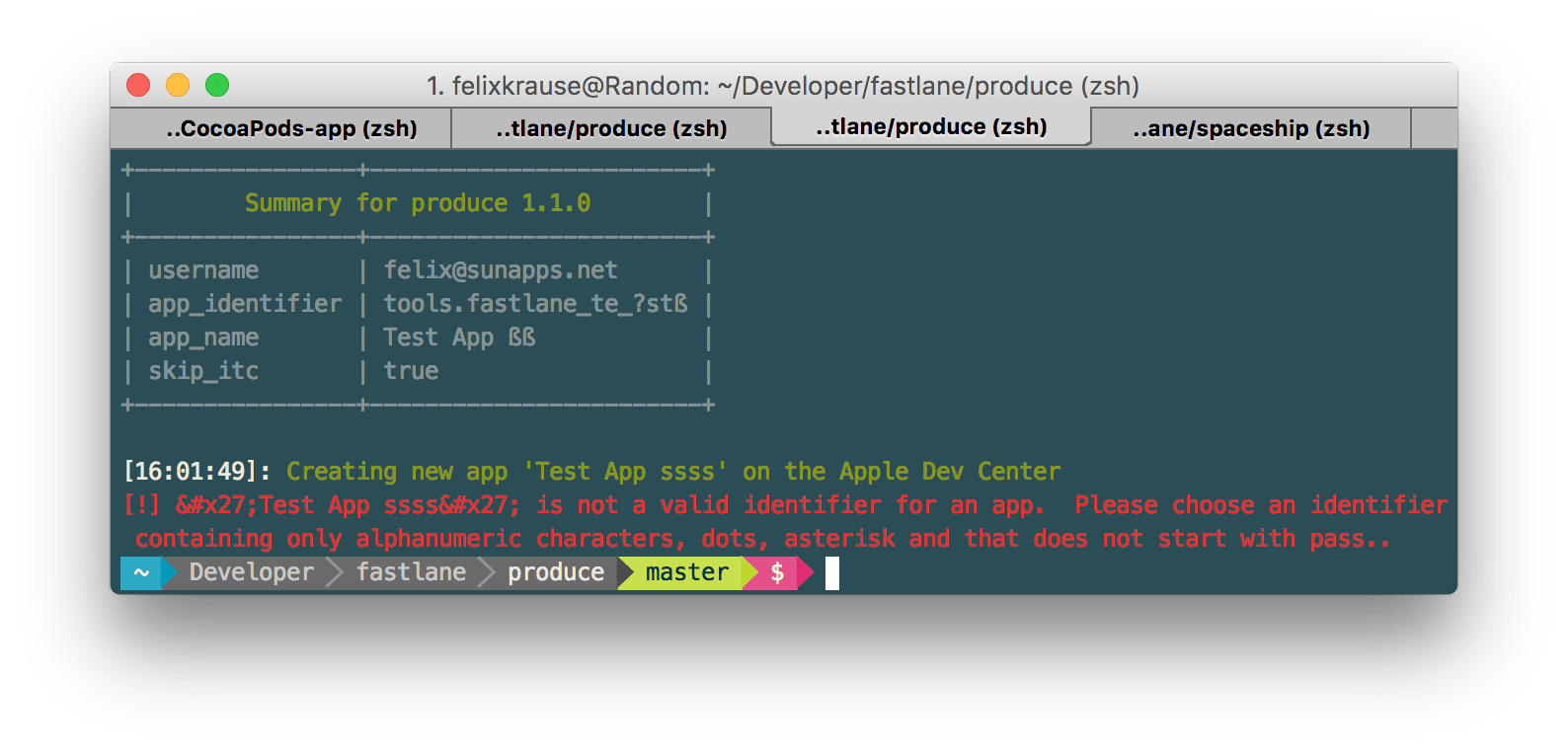

The left screenshot shows an early version of fastlane, compared to how fastlane shows error messages today. Not only how you present the error message, but its content is really important: Make sure the message explains the error well enough and ideally even include instructions on how to fix it.

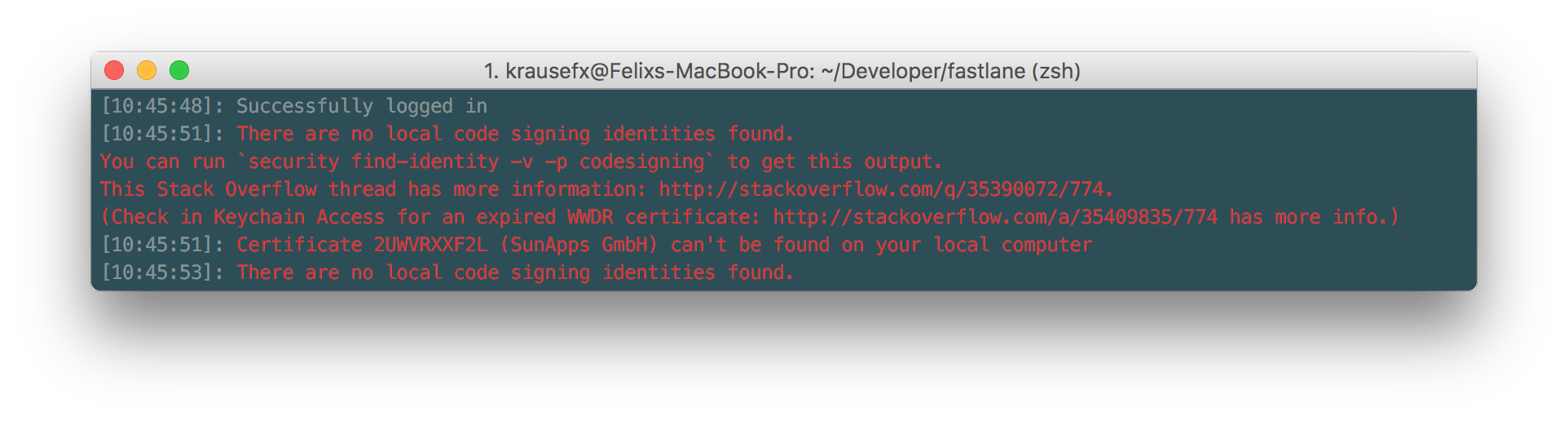

In fastlane we even link to StackOverflow replies and make sure to include all necessary information to debug an issue. In this example we show the certificate ID and team name.

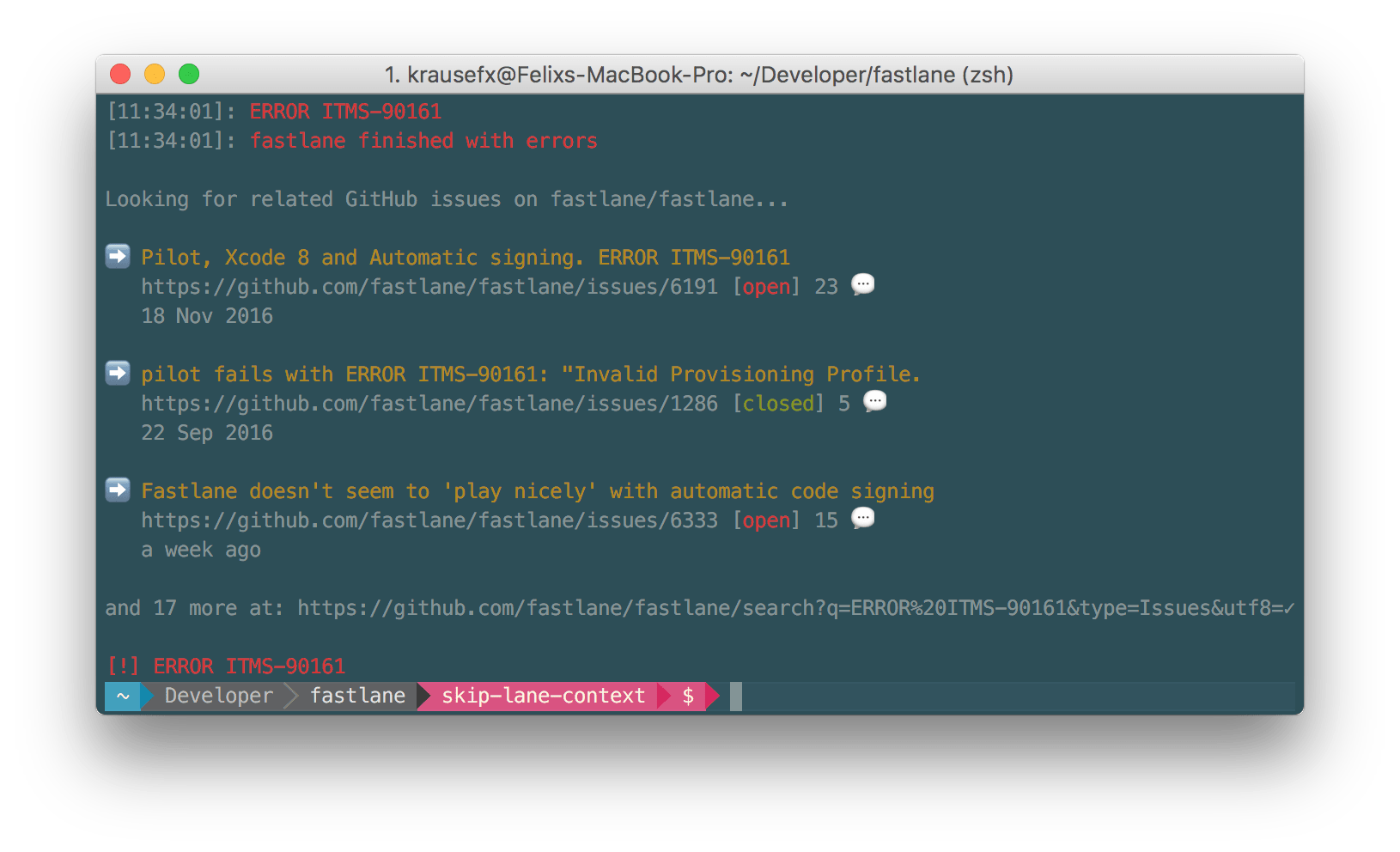

Make it easy to find existing issues

When you receive a cryptic error message, what’s the first thing you do? Usually you search on the GitHub repo page, or google for the message. You as a project maintainer should make it easy as possible for the user to do so. That’s why @orta started gh_inspector, a Ruby gem to show related GitHub issues right in the user’s terminal. Whenever fastlane runs into an unexpected situation, it will not only show similar GitHub issues, but also print out the GitHub search URL. The long-term plan is to also support StackOverflow questions (see #13)

Whenever fastlane runs into an unexpected error it automatically shows similar issues on GitHub

Whenever fastlane runs into an unexpected error it automatically shows similar issues on GitHub

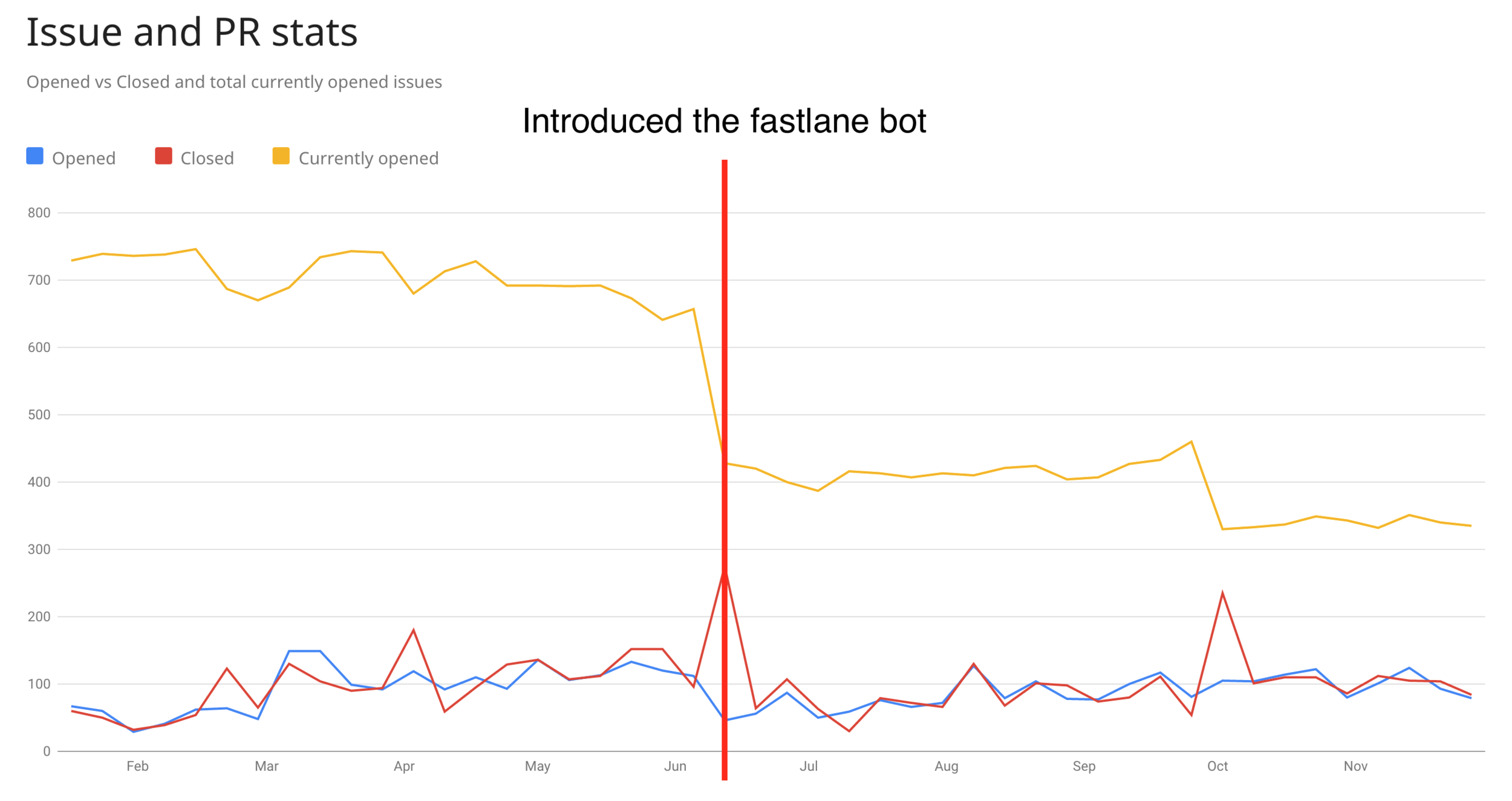

Use of bots

I’m not a big fan of bots and automated messages, however as soon as you reach a certain scale you need to have some automated systems to reduce the support load.

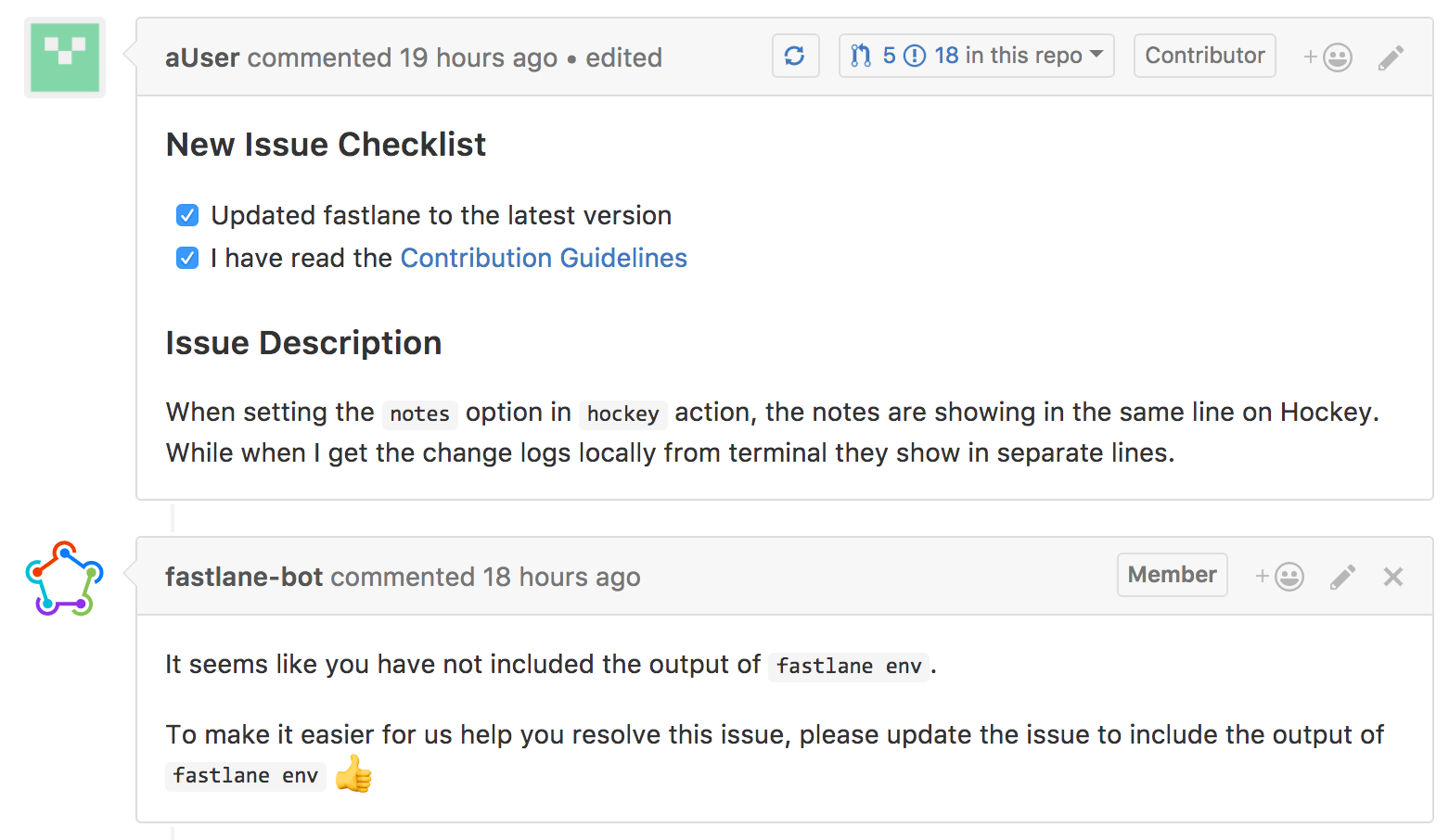

Ensuring all required information is available

Providing all information when submitting a bug report is hard, even as a software engineer. GitHub recently introduced ISSUE_TEMPLATE.MD, that auto-fills the “New Issue” form with instructions on how to file an issue. However most people ignore the instructions.

Using the fastlane-bot we ensure all required information is available, and if not, tell the user how to provide them.

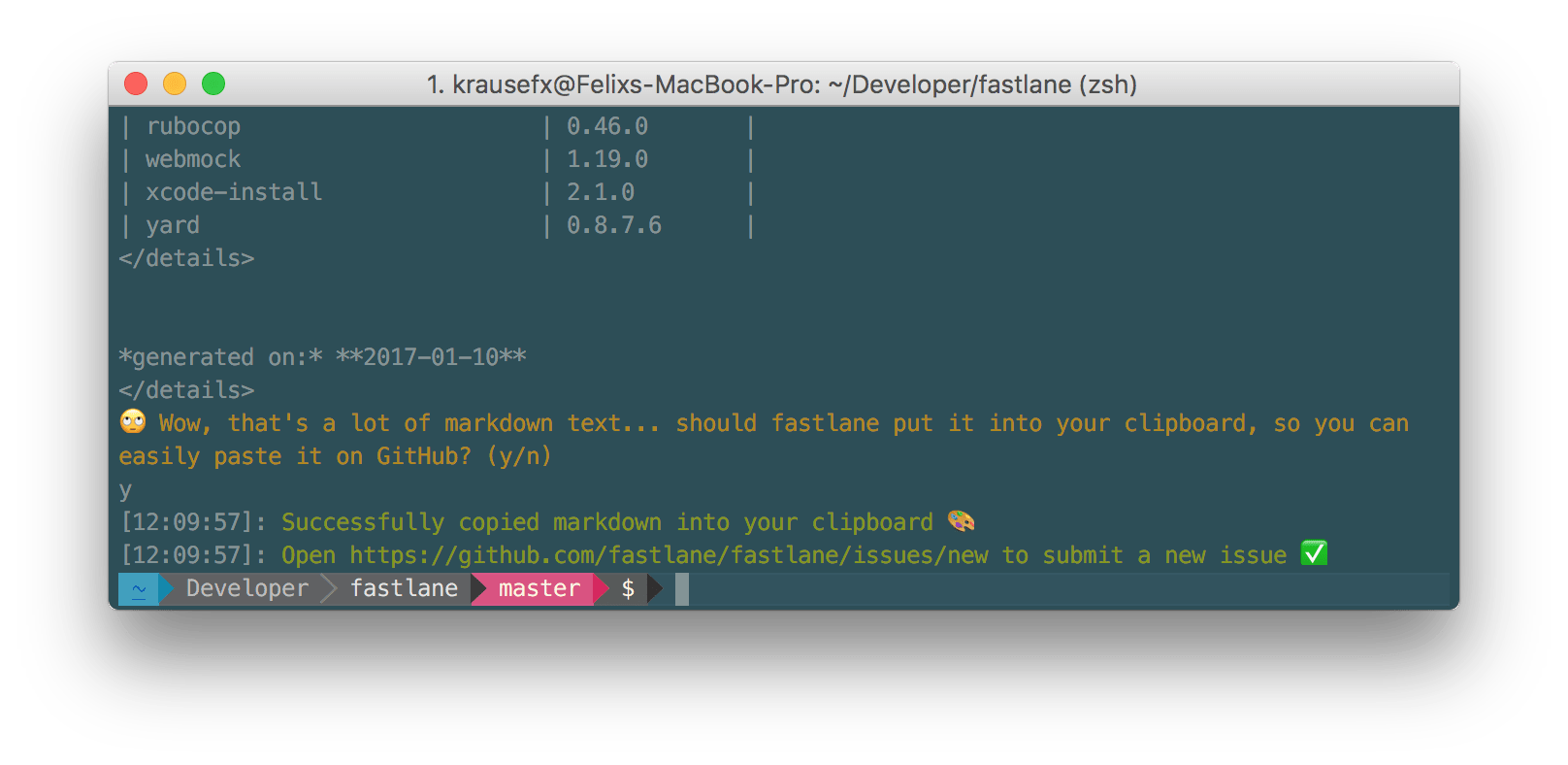

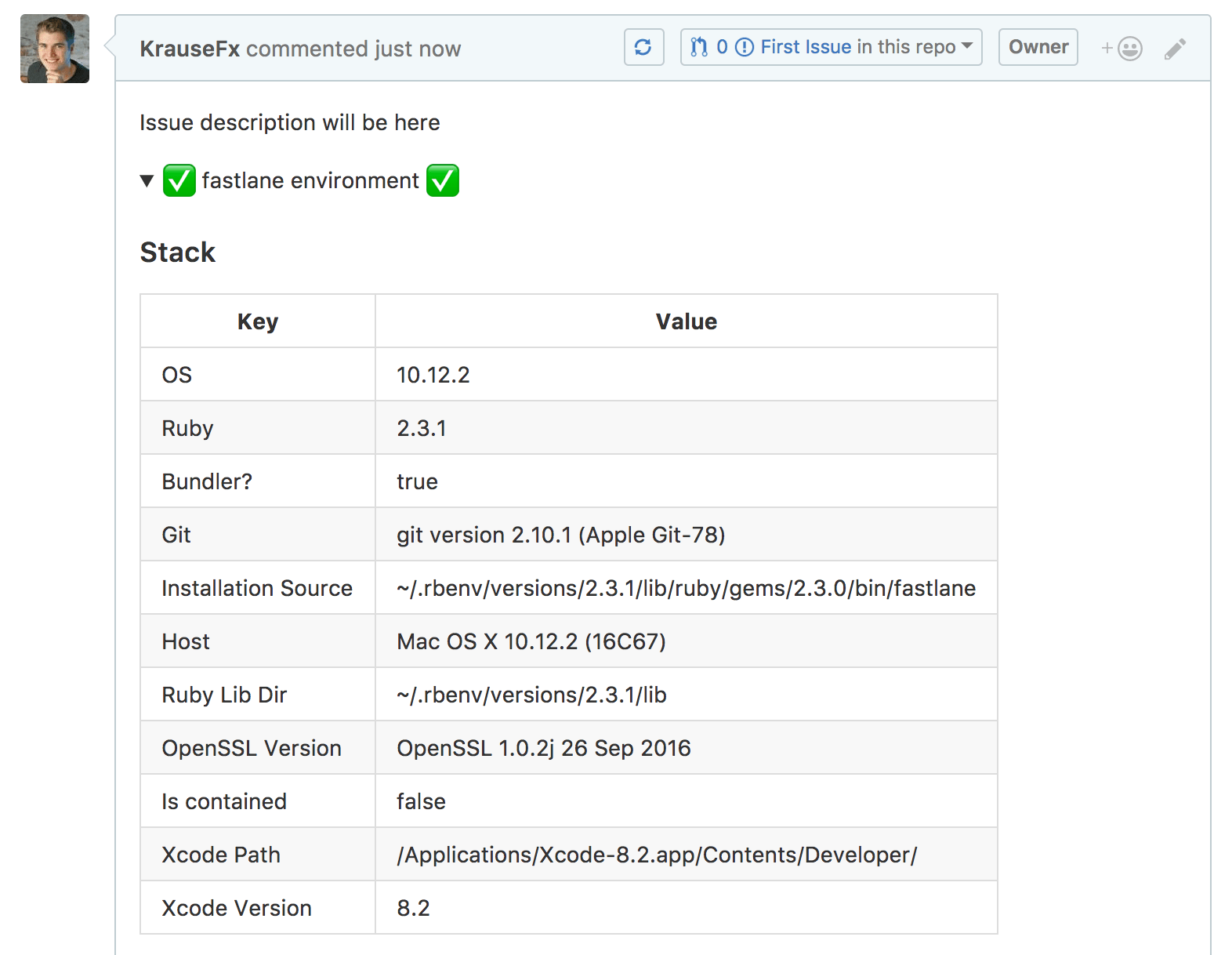

With that, fastlane also supports the fastlane env command that prints out all relevant information:

The fastlane env command collects all relevant system information, like your Ruby environment, OpenSSL version and used fastlane plugins, ready to be posted on GitHub.

Helping users is so much easier if you have all the information right there, including all configuration files, other dependencies and version numbers.

Answers based on keywords

If you receive similar issues very often, you should step back and work on fixing the underlying issue or making usage more clear. If 10 users submit a specific kind of issue, hundreds of other users felt the same way but didn’t take the time to submit an issue.

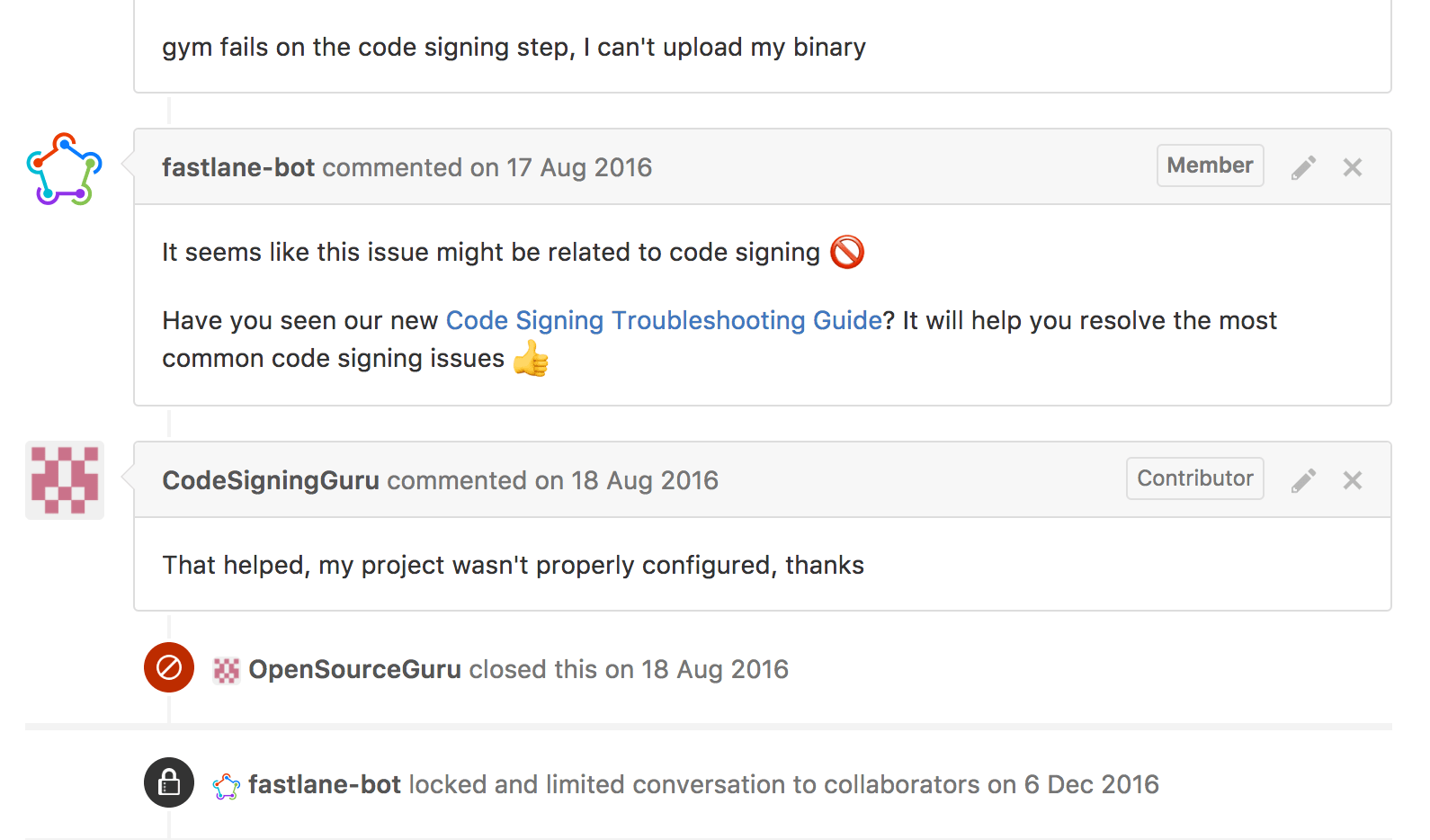

In the case of fastlane, many issues are related to code signing (yeah), however there is no ultimate solution to fix all issues as of now (codesigning.guide is the easiest one so far). We wrote an extensive guide on how to setup code signing and how to troubleshoot problems. As with most things, users don’t like reading manuals, unless you link them to the right spot, which is exactly what the fastlane-bot does in that case.

Many times just linking people to the right docs already helps

Many times just linking people to the right docs already helps

Stale issues

The key to handle support for large-scale open source projects is to keep issues moving. Try to avoid having issues stall. If you’re an iOS developer you know how frustrating it can be to submit radars. You might hear back 2 years later, and are told to try again with the latest version of iOS. Chances are high you have no way to reproduce the issue again for multiple reasons:

- The user tried your software, submitted the issue, and went with a different solution in the meantime

- The user already found a workaround, and doesn’t care about spending more time on this issue

- Many engineers switch companies and projects frequently

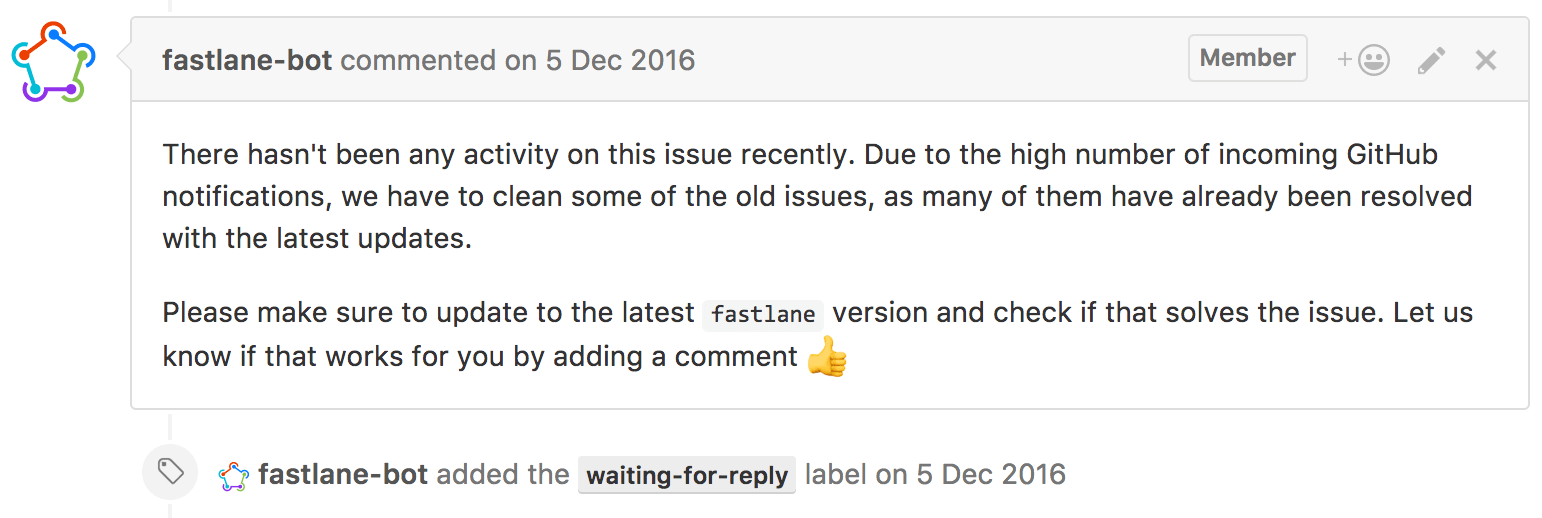

Having a bot can ensure that issues are still relevant and reproducible. The fastlane-bot automatically asks if an issue is still relevant with the most recent fastlane release after just 2 months.

If no participant of the issue replies to the bot within a month, the issue gets auto-closed, with a note that a new issue can be submitted to continue the discussion.

About a month after closing the issue, the bot locks the conversation to repository admins only.

Locking resolved and inactive issues

Locking conversations of resolved, inactive issues is a great way to avoid re-surfacing GitHub issues from old releases. In the case of fastlane the following happened a lot in the past:

- Users would comment on issues that are not related to their problem, however sound similar

- Users would comment on issues with a lot of subscribers from a long time ago, triggering unwanted email notifications for people who already found a solution

- The

fastlane-botdoesn’t ensure if all required information is provided for single comments, but only for new issues - Users would add “me too” commented without providing any details of the current problem they’re having

By telling users to submit a new issue, you properly go through the complete lifecycle of an issue:

- User submits issue

- The

fastlane-botensures all required information was provided - Actual discussion around the issue

- Issue gets resolved or auto-closed due to inactivity

Responding to pull requests

The sections above mostly covered issues, but a very essential part is also responding to pull request. You have certain rules for your projects, like automated tests, code style and architecture. Many of those things are already checked by regular CI systems, and the build for the PR fails if the requirements aren’t met.

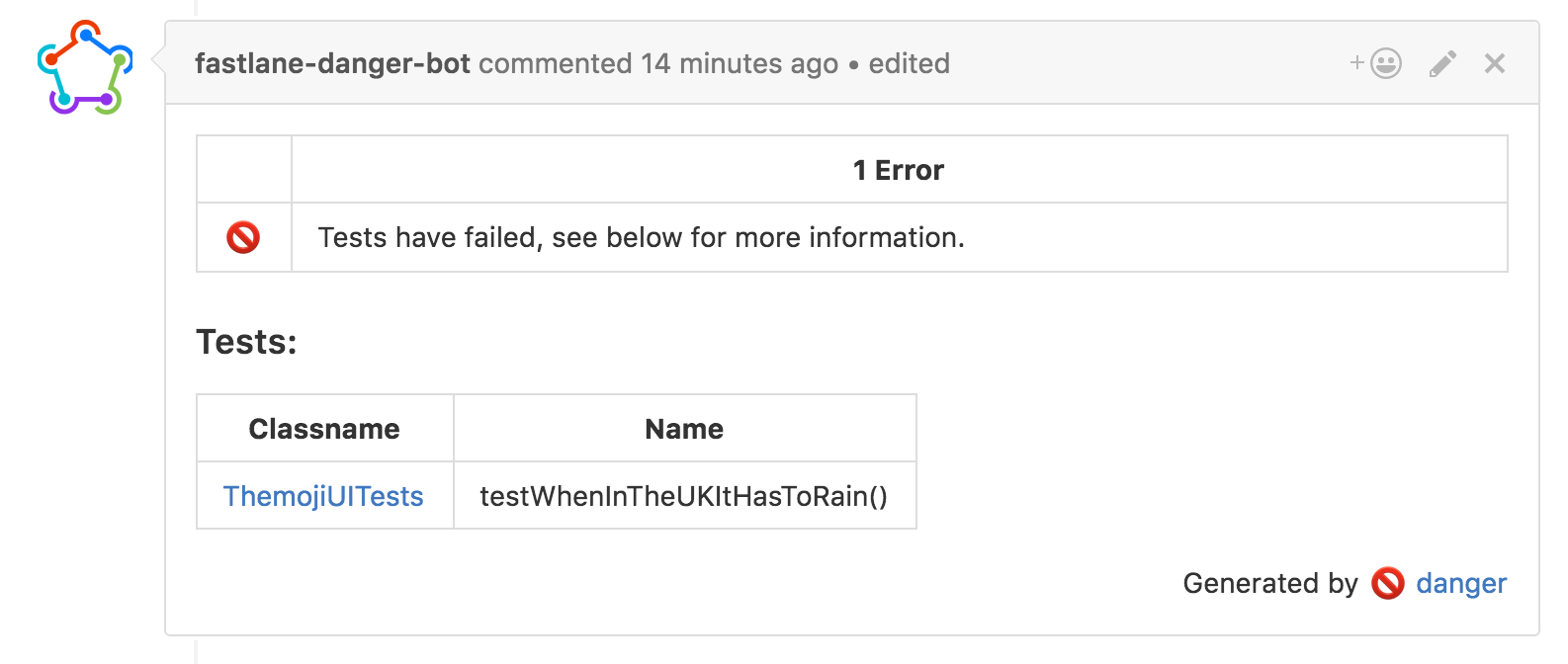

However tests don’t ensure the way how changes are introduced (= the delta). That’s why @orta and I set out to build danger, a tool that allows you to define rules for code changes. Some examples:

- Post test failures right on GitHub so that contributors don’t have to scroll through the CI output

- Show a warning when certain files get modified

- Require new tests when more than 20 lines were modified

- And many more

PR and Run

This is something you can see in many open source projects, someone takes the time to submit a pull request, the build is failing but the author doesn’t update the PR. The reason for that is that there is no GitHub notification when their build fails, so you as a project maintainer now have to be the “bad person” to tell the developer to fix the tests. That’s time you spend on something, that should be completely automated. By using danger, you can have the CI post the test results right on GitHub triggering a GitHub email notification.

Steering the direction

It’s 🔑 to work into the same direction and have a shared vision. For open source project, most communication happens asynchronously instead of having meetings. Because of that, it’s a little harder to stay focused on going into the right direction.

Many bigger open source projects introduced a VISION.md (e.g.fastlane,danger) that describes the bigger-picture goal of a project and the overall philosophy.

This enables contributors of the project to say “No” to feature requests or PRs by referencing the written agreement in the repository. The beauty of this approach is also that everyone has the opportunity to submit PRs for the VISION.md document to propose changes in the policies.

Scaling contribution

As your project grows you need more people joining you on maintaining the project and pushing it forward. You want to increase the bus factor as your project grows, meaning more and more people know how the project works and can commit code. There are some great approaches out there, like the moya contributing guidelines by Ash Furrow. Ideally the project operates without any help from you.

Code of Conduct

With a growing community, you also need to ensure developers are in a safe environment. One action you should take very early in your project is to add a Code of Conduct (more information by Ash)

Onboarding instructions

Make it very easy for engineers interested in submitting code changes to set up their development environment. If you’re not a mono-repo yet (:trollface:), you might need a repo to quickly set up all the other repos, e.g. CocoaPod’s Rainforest, fastlane’s countdown(now deprecated)

Keeping your code base simple

This is something not many open source projects consider: the more complex the software architecture is, the more difficult it is to get started coding and less people are able to contribute. Instead of using the latest Ruby magic to save 4 lines of code, use the easiest to understand technique to solve a problem, making it easier for people to spot issues and contribute fixes and improvements.

Be welcoming and friendly

This has been top priority for me since starting fastlane. Always be as friendly as you can. Thank people for submitting issues and PRs. Ask people for help or clarification if needed.

Enabling your users to extend your project

When scaling your project you have to say “No” to many new features and ideas. Instead you need to focus on what your software is best at. However most software would be very limited if there was no way to extend it. Depending on the size of your community, there are two good way to achieve that.

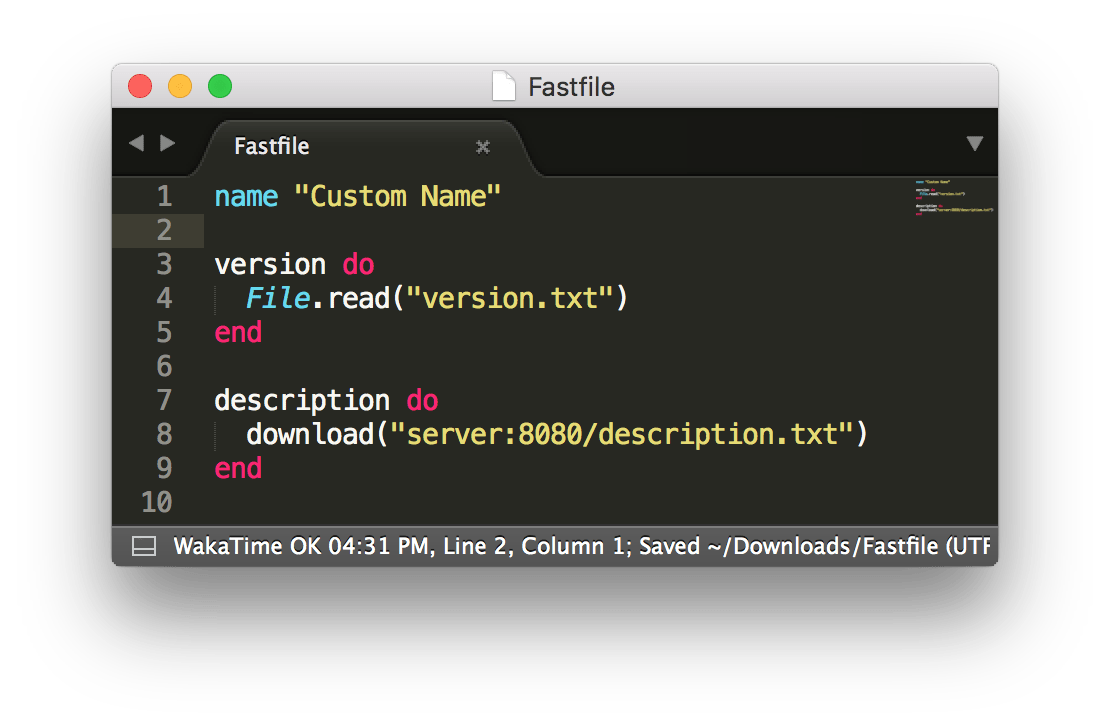

Offer dynamic configuration files (ala DSL)

Many Ruby-based open source projects, including fastlane, CocoaPods and Bundler, offer a DSL that allows developers to implement a very dynamic configuration. Instead of having static values like it is the case in JSON or yml files, you can execute code in a Fastfile, Podfile and Gemfile. This is extremely useful to fetch or generate values on demand, like accessing an internal server for the latest app description.

Allow local extensions

This is how we started out with fastlane: when a user needed an integration for a third party or internal service that isn’t available yet, they can easily build and use a local action without having to touch the actual fastlane code base. Most of the times, the developers would store their local actions in their git repository.

Allow the community to extend and build on your project using plugins

Allowing local changes works great for a while, until users want to share their integrations with the rest of the community. Once that’s the case you need to provide an ecosystem (kind of like a marketplace) for developers to share their integrations.

While it’s not possible for all kinds of projects, building a plugin architecture enables your project to advance at a much faster pace. Your dependency graph will stay slimmer, you might receive less PRs adding new features and your core code base can stay smaller.

Of course you can build your own dependency resolving, however think twice before doing so. There might be a great dependency manager available you can use to implement your plugins.

At fastlane we use RubyGems and bundler to make it easy for people to distribute and use plugins. As a result there are already 120 third party plugins available within just a few months.

Wrapping up

Scaling open source projects is hard. Really hard. There are lots of challenges you’ll solve while scaling up. Ideally you’re not the person having to solve all problems that are caused by a growing project, but have core contributors helping you. Good open source projects stay alive for a really long time and you can have an enormous impact on developers and companies around the world with it. If you face challenges, don’t give up, ask the community for help. I personally have never worked on a project with such a great impact, and I feel extremely lucky to work on the right thing at the right time.

I described the above with the assumption that you would use GitHub for your open source projects. There are many alternatives out there, however to simplify the above text I decided to use GitHub with the terms “Issues” and “Pull Requests”.

fastlane is joining Google

It’s only been a bit over year that fastlane joined Fabric at Twitter, which enabled me and the team to build even more awesome things around fastlane, just some examples:

- A web-app to build your fastlane configuration

- A pre-packaged fastlane, to have all dependencies bundled

- fastlane plugins, a new way to create powerful actions and extend fastlane

- Full 2-factor support for Apple IDs

- Upgraded fastlane to be a mono-repo

- Launched the new docs.fastlane.tools page

Today it’s time for the next big step for fastlane: fastlane - along with the Fabric platform - is joining Google, working together with the Firebase team. The two teams are committed to building the best tools to help developers build better apps. fastlane will stay an open source project as part of that mission.

I’m super excited about this opportunity, and can’t wait for what we can all build together.

Tags: fastlane, google | Edit on GitHub

Writing automated tests for your documentation

The 2 favourite topics of every engineer are usually unit tests and documentation. The last few weeks I’ve put some thoughts in how to combine those two things for the ultimate developer joy.

Why should I write tests for my documentation?

- You might forget to update parts of the documentation when you update your API or interface

- Spelling mistakes happen in code samples

- You want to make sure you don’t introduce any regressions with a new release

With the launch of the new docs.fastlane.tools website, we took the time to set up a proper documentation system based on markdown files, converted to a static HTML page using MkDocs. By having full control over the generated HTML code, and going 100% open source on GitHub, you can do powerful things:

- Fail the build when a page got removed from the index using danger (see Dangerfile)

- Generate redirects when a page got moved (see generate_redirects.rb and available_redirects.rb)

- Make sure the repo is in a valid states, and all documentation follows the convention

- Write tests for your documentation

Tests for documentation, what does this even mean?

Just like with your actual code base, you want to be sure that your repository is in a valid state. The same applies for your documentation. Is your latest documentation up to date, and does it work as expected? Does it work with your latest release?

The first time I thought about running tests for documentation I thought only about the code samples. However you can write tests for a lot of more things. For example you want to ensure that all your assets are in the right sub-directory, that all referenced images and markdown files are available and follow your naming scheme.

Some examples of what you can do:

Validate file names

Ensure that all file names follow your convention - this is especially important if the file names are visible in the URL.

private_lane :ensure_filenames do

UI.message "🕗 Making sure file names are all lowercase..."

Dir["docs/**/*.md"].each do |current_file|

if current_file =~ /[A-Z]/

UI.user_error!(".md files must not be upper case, use a dash instead (file '#{current_file}')")

end

end

UI.success "✅ All doc files are properly named to not be camel case"

end

Ensure every page has a header

fastlane docs require a title on each page to be consistent.

private_lane :ensure_headers do

UI.message "🕗 Investigating all docs files and their headers..."

exceptions = ["docs/index.md"]

Dir["docs/**/*.md"].each do |current_file|

next if exceptions.include?(current_file)

unless File.read(current_file).start_with?("#"))

UI.user_error!("File '#{current_file}' doesn't start with #"

end

end

UI.success "✅ All doc files start with a header"

end

Ensure all image assets are available and in the correct folder

Automatically verify all referenced image assets are available and stored in the right folder, find the source here.

Ensure spelling of certain words

Recently we switched from fastlane to fastlane in markdown files, so we want to ensure all new docs use the new way of spelling.

private_lane :ensure_tool_name_formatting do

UI.message "🕗 Verifying tool name formatting..."

require 'fastlane/tools'

Dir["docs/**/*.md"].each do |path|

content = File.read(path)

Fastlane::TOOLS.each do |tool|

if content.include?("`#{tool}`")

UI.user_error!("Use _#{tool}_ instead of `#{tool}` to mention a tool in the docs in '#{path}'")

end

if content.include?("_#{tool.to_s.capitalize}_") || content.include?("`#{tool.to_s.capitalize}`")

UI.user_error!("fastlane tools have to be formatted in lower case: #{tool} in '#{path}'")

end

end

end

UI.success "✅ fastlane formatting is correct"

end

Verify code samples

How many times have you copied a code sample to try it out, just to find out it doesn’t work with the latest release? There are various reasons for this, and without tests there is almost no way to avoid this. The error can be as simple as a spelling mistake.

By having full control over your documentation, you can easily iterate over all your code samples, and make sure they work as expected.

For fastlane we found 28 errors just in the actions documentation, most commonly syntax errors or just simple spelling mistakes in parameter names.

For all the checks mentioned below, the source is on the fastlane docs repo.

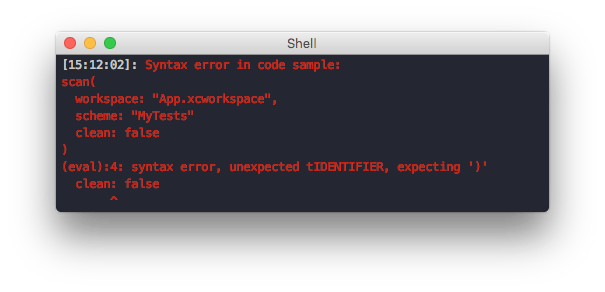

Catch syntax errors in code samples

Nothing is more frustrating than copying a code sample and having to fix the syntax to make it work. Most users won’t spend the time to look into how they can contribute to your docs to fix the error.

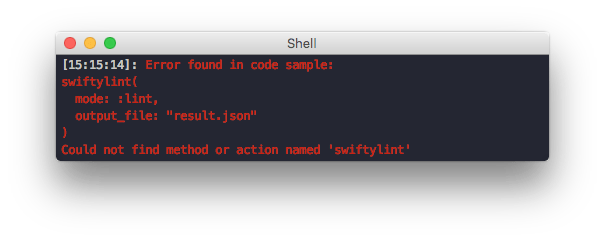

Catch unavailable actions or methods

For fastlane most code samples call certain actions or integrations. Using tests we ensure that this action is available and correctly spelled.

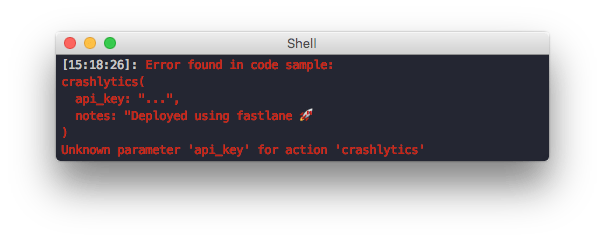

Verify action parameters

Most fastlane actions allow passing of named parameters. We now automatically verify that all parameters are available to use.

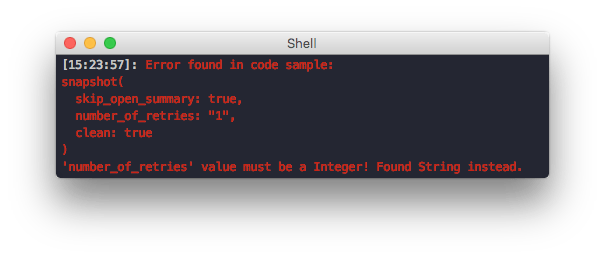

Verify parameter types

Every fastlane parameter has a type defined, which fastlane validates on run-time. It’s easy to get a type wrong in the documentation, so we now validate those too.

When to run tests for your docs?

There are 2 points where you want to verify your docs are valid and up to date:

- When you push a new release of your software (deploy script of your software)

- When you update your documentation (CI test script of your docs)

So whatever introduced a regression, the build will be failing and you can’t merge the change into master.

Where to go next

These are just some things you can do with tests for your documentation, however I’m sure there are so many things you can automatically test and verify every time your code changes. Let me know if you have any ideas on what other crazy things you can do.

Tags: fastlane, tests, automated, docs | Edit on GitHub

'trainer' - the simplest way to generate a JUnit report of your iOS tests

If you’re running tests for your iOS code base on some kind of Continuous Integration, you usually have to generate a JUnit file to report the test results, including error information, to your CI system. Until now, the easiest solution was to use the amazing xcpretty, which parses the xcodebuild output and converts it to something more readable, additionally to generating the JUnit report.

Since there were some difficulties with the new Xcode 8, Peter Steinberger and me had the idea to parse the test results the same way Xcode server does it: using the Xcode plist logs.

trainer is a simple standalone tool (that also contains a fastlane plugin), which does exactly that: Convert the plist files to JUnit reports.

By using trainer, the Twitter iOS code base now generates JUnit reports 10 times faster.

To start using trainer, just add the following to your Fastfile:

lane :test do

scan(scheme: "ThemojiUITests",

output_types: "",

fail_build: false)

trainer(output_directory: ".")

end

By combining trainer with danger, you can automatically show the failed tests right in your pull request, without having to open the actual output.

For more information about when to use trainer, check out the full blog article on PSPDFKit.